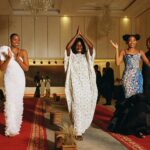

Historic launch in Brazzaville

Under the midday sun of 4 December in Brazzaville, applause filled the courtyard of Mfilou’s municipal hall as the NGO Johny Chance unveiled Congo’s first local sunscreen factory dedicated to people with albinism, a community for whom skin cancer remains the leading fatal threat.

The compact unit plans to roll out 4,000 tubes in its maiden year 2026, enough to protect more than 1,000 beneficiaries across the nation’s twelve departments, all free of charge thanks to a model linking health solidarity and made-in-Congo industrial know-how.

Dermatologists estimate that in central Africa ninety out of a hundred people with albinism will develop precancerous lesions before thirty, a statistic repeatedly cited by the World Health Organization and echoed by local clinicians at the launch ceremony.

Until now, most Congolese families had to rely on imported lotions priced well above 10,000 CFA francs, far beyond the monthly income of many, forcing some to improvise with shea butter or stay indoors at the expense of school and work.

Inside the sunscreen factory

Cheerful but focused, pharmacist-engineer Christophe Jean-Marie, envoy of the Pierre Fabre Foundation, guided visitors through stainless-steel reactors mixing zinc oxide, mineral filters and locally sourced karité oil, a formula refined during two years of pilot batches in Toulouse and Bangui laboratories.

Every tube carries a bright blue palm logo referencing Brazzaville’s river identity alongside the emblems of the ministry of Social Affairs and the consul of San Marino, underlining that official support remains at the heart of the project’s messaging.

Jhony Chancel Ngamouana, founder and himself born with albinism, spoke with emotion, recalling childhood days hiding under mango trees to avoid blistering burns. He sees the factory as proof that ‘we are not statistics but actors of our own protection’.

Lives changed by local protection

Mélanie, a 22-year-old student from Oyo, tested the first batch on her arms. She described a non-greasy texture and a ‘soothing smell of cocoa’. For her, the most important change is psychological: ‘Knowing the tube is made here means it will not run out’.

Parents’ associations also welcomed the move, noting that absenteeism among children with albinism spikes during the long dry season. By securing regular supply, activists hope school attendance and exam performance will rise, reinforcing government goals on inclusive education.

Local economic analysts underline another angle: the unit employs 15 young laboratory technicians from Mfilou district, half of them women, offering stable jobs in a city where youth unemployment hovers around 20 percent according to the national statistics institute.

Official backing and global standards

Minister Irène Marie-Cécile Mboukou Kimbatsa pledged logistical help for nationwide distribution, praising ‘a citizen initiative fully aligned with the Head of State’s social programme’. Her cabinet considers integrating the sunscreens into future universal health insurance baskets to guarantee continuity.

In a short address, Brazzaville’s mayor Bibiane Itoua reminded the audience that stigma often begins with a sunburn in the street. ‘Protect the skin and you protect dignity’, she said, announcing an awareness caravan through markets and bus terminals.

Marcelo Della Corte, honorary consul of San Marino, warned that success will depend on sustained access to raw materials such as titanium dioxide, subject to global supply fluctuations. He suggested exploring Congolese mining by-products to localise the entire value chain.

The Pierre Fabre Foundation, already active in Madagascar and Chad on similar projects, will conduct quarterly quality audits and continuous training via tele-pharmacy platforms, ensuring the Congolese batches meet the European Pharmacopeia standard SPF 50, organizers confirmed.

Next steps for nationwide impact

Looking ahead, Jhony Chance plans to couple sunscreen supply with dermatology outreach camps in remote districts such as Likouala and Sangha, where river transport challenges remain acute. Mobile clinics would screen early lesions and teach correct application techniques.

For Mélanie and hundreds like her, the small plant means more than chemistry; it signals recognition. As the ribbon fluttered in the heat, she whispered, ‘Next year I will walk to campus at noon, face up’. In Brazzaville, that simple gesture feels revolutionary.

According to geneticist Dr. Prisca Massamba of the Congolese Foundation for Medical Research, the country counts an estimated twelve thousand people living with albinism, though exact numbers remain elusive because many births occur in rural zones without systematic registration.

Her team will track melanoma incidence before and after the sunscreen roll-out, creating a rare long-term dataset for sub-Saharan Africa that could inform regional health policy and, supporters believe, attract more pharmaceutical investment to Congo’s budding life-science sector.

Civil society networks such as Collectif Ndzoto have already scheduled February forums in Pointe-Noire, Dolisie and Owando to discuss sun safety, celebrate positive representations in music videos and distribute illustrated guides translated into Lingala and Kituba, ensuring messages cut across linguistic and cultural lines and even sign language sessions planned.