A continent-wide diplomatic choreography

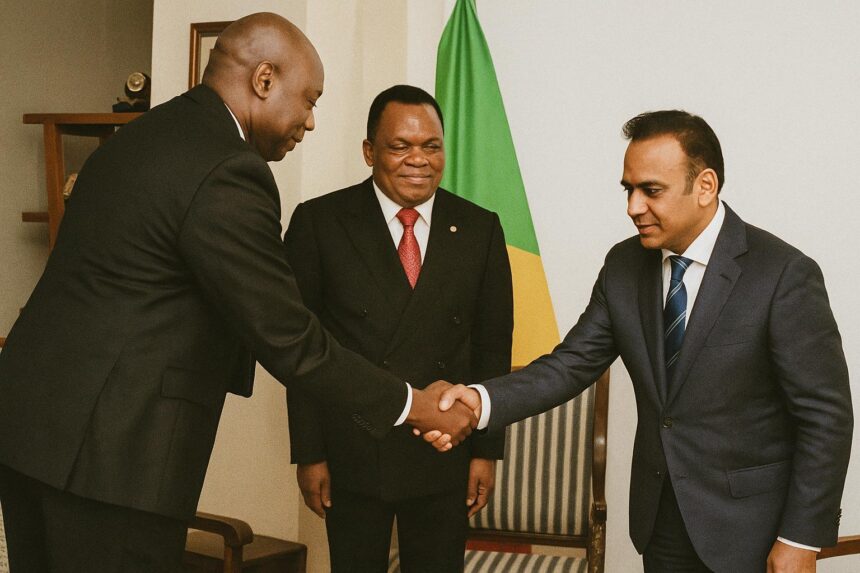

The Congolese diplomatic corps has spent the height of the austral winter weaving an intricate web of high-level consultations from Luanda to Port-Louis. Charged by President Denis Sassou Nguesso with rallying African endorsement for Firmin Édouard Matoko’s bid to become UNESCO’s next Director-General, Foreign Minister Jean-Claude Gakosso completed a six-nation swing that culminated on 25 July in the Mauritian capital. At each stop he delivered sealed letters from the Congolese Head of State, a traditional instrument of African diplomacy that underscores both respect and urgency. Observers in Pretoria and Windhoek note that the choreography reflects a growing belief in Brazzaville that continental solidarity must be brokered in person if it is to translate into votes during the secret ballot in Paris.

The decision to begin in Luanda was not merely geographic convenience. Angola currently enjoys an influential seat on UNESCO’s Executive Board, and its President João Lourenço has publicly championed Lusophone-Francophone bridges within multilateral bodies. By demonstrating cultural and linguistic versatility early in the tour, Brazzaville signalled that Matoko’s candidacy intends to transcend sub-regional blocs.

Matoko’s profile and regional resonance

A former UNESCO Assistant Director-General for Priority Africa and External Relations, Firmin Édouard Matoko commands a résumé that few rival aspirants can match. Educated in Brazzaville and Paris, he steered several UNESCO flagship initiatives on literacy, freshwater sciences and intangible heritage. According to internal UNESCO evaluation reports consulted in Paris, his tenure between 2014 and 2022 posted a 23 percent increase in extra-budgetary contributions earmarked for the continent. Congolese officials quietly contend that those figures furnish compelling evidence of managerial prudence.

Regional resonance matters. In Port-Louis President Prithvirajsing Roopun, himself a former educator, praised Matoko’s “pedagogical diplomacy” in front of local media, a phrase swiftly echoed by Congolese outlets. While official endorsements remain confidential until transmitted to UNESCO’s Secretariat, analysts in Addis Ababa observe that small-island developing states value Matoko’s climate-education advocacy, viewing him as a bridge between African and oceanic priorities.

African multilateralism recalibrated

Brazzaville’s démarche also reveals a broader recalibration of African multilateral strategy. The African Union has yet to pronounce on a single continental candidate, a vacuum that favours early movers. In an interview granted en route to Windhoek, Minister Gakosso stated that “Africa must no longer appear in Paris divided by linguistic fault lines; we offer a candidacy forged in consensus”. His emphasis on unity echoes the AU’s 2023 Summit communiqué urging member states to present consolidated slates for top United Nations positions.

Political scientists at the University of Cape Town discern a second, more subtle layer: Congo-Brazzaville is positioning itself as an honest broker among the competing aspirations of West, Central and Southern Africa. The inclusion of Mauritius—outside the customary Central African orbit—was therefore strategic, indicating that Brazzaville seeks to knit together the continent’s Anglophone, Francophone and Lusophone constituencies. Such outreach gains added significance in light of UNESCO’s own emphasis on cultural diversity.

Navigating global dynamics in Paris

Securing African unanimity is necessary but not sufficient; the decisive vote will come from UNESCO’s 58-member Executive Board, where European and Asian states wield considerable influence. Diplomats posted to UNESCO’s Paris headquarters recall that the 2017 contest saw Arab and European blocs alternate between coalition and competition before converging around Audrey Azoulay after five inconclusive rounds. Against that backdrop, Prime Minister Anatole Collinet Makosso is slated to extend the campaign beyond Africa in September, with discreet stopovers expected in Riyadh, Madrid and Tokyo.

International reactions remain cautiously favourable. A senior Scandinavian delegate, speaking on condition of customary anonymity, noted that Matoko’s record on organisational reform “ticks many of the boxes we prioritise, notably geographic equity and budget transparency.” Nonetheless, he hinted that European capitals will scrutinise governance pledges before committing.

Prospects and implications for Congo’s soft power

Victory would mark the first time a Congolese national heads a specialised UN agency, thereby amplifying Brazzaville’s soft-power toolkit. Domestic commentators already liken the effort to the country’s 2021 chairmanship of the Congo Basin Climate Commission, which attracted substantial green financing. Should Matoko prevail, Congo’s educational and cultural diplomacy could benefit from privileged agendas within UNESCO, including capacity-building programmes that align with the government’s 2022–2026 National Development Plan.

For now, the campaign remains in its courtship phase. Yet the methodical sequencing of visits, the emphasis on African consensus and the candidate’s technocratic profile suggest a bid crafted with a keen understanding of twenty-first-century multilateral arithmetic. In the words of Minister Gakosso, offered after his audience with Mauritian officials, “Our ambition is modest in tone but lofty in scope: to see Africa contribute solutions, not grievances, to the global commons.” His remark captures the dual objective animating Brazzaville’s waltz across the continent—advancing national prestige while nudging multilateral governance towards a more equitable horizon.