Pink Card Origins and Legal Standing

The faintly peach-tinted insurance certificate nicknamed the CEMAC Pink Card rarely attracts attention at border checkpoints, yet its legal force binds six Central African states. Since 2000, motorists in the Republic of Congo and its neighbors have been obliged to carry the document alongside domestic liability stickers.

Created by a protocol signed in Libreville on 5 July 1996, the card extends compulsory third-party motor insurance across Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville. The goal is straightforward: assure quick compensation for accident victims while fostering sub-regional economic integration.

Yet, two decades later, the scheme still languishes in relative obscurity. Customs officers sometimes ignore it; drivers often confuse it with local documents; and foreign insurers occasionally request redundant guarantees. Confronted with these frictions, CEMAC’s Council of Bureaux mandated national branches to intensify public outreach.

Robert André Elenga’s Outreach Drive

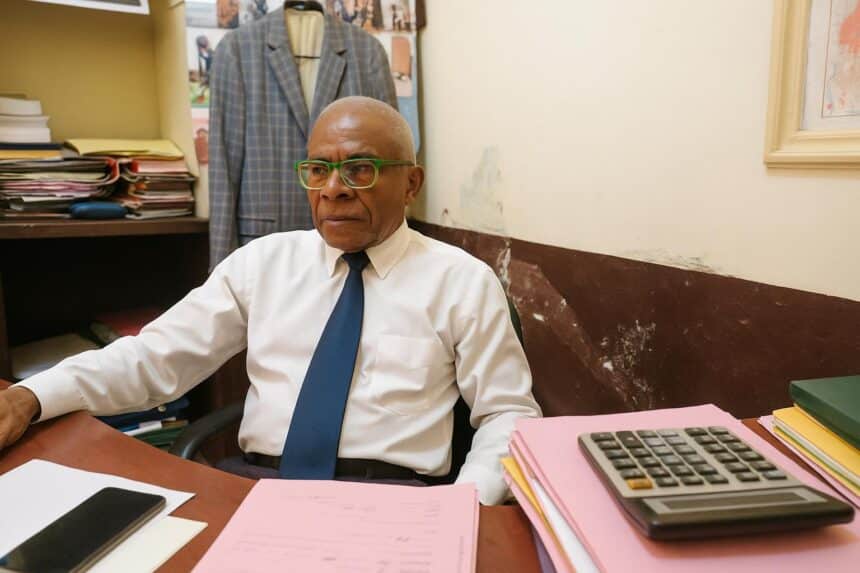

In Brazzaville’s bustling Moungali district, insurance veteran Robert André Elenga now personifies that task. As secretary-general of the Congolese Pink Card bureau, he began a street-level sensitisation campaign this spring, speaking at taxi ranks, driver unions and police briefings, patiently explaining the cross-border value of the laminated slip.

His message is pragmatic. The card, he notes, spares Congolese hauliers from depositing costly cash bonds in Douala or Libreville after minor fender-benders, while protecting travellers from vehicle impoundments. “It is our passport for mobility,” Elenga told a gathering of truckers in April, according to local media reports.

Authorities appear receptive. The Congolese National Police announced that checkpoint supervisors will receive refresher courses on Pink Card verification. The Association of Insurers of Congo has meanwhile distributed thousands of multilingual brochures, aligning with a wider CEMAC blueprint endorsed at a Council of Ministers meeting in Malabo.

Regional Mobility and Economic Stakes

At stake is more than administrative tidiness. The Bank of Central African States estimates that road freight supports nearly 35 percent of intraregional trade volume. Smooth insurance recognition could therefore cut transaction costs, accelerate delivery schedules and bolster the competitiveness of Congolese timber, fuels and agricultural exports.

Regional businesses echo that view. A logistics manager at Pointe-Noire’s port says trucks occasionally idle for days at Cameroonian posts because officers doubt insurance coverage. Each delay, he argues, reverberates along supply chains, inflating prices in landlocked Chad and Central African Republic, eroding consumer confidence.

Economic think tanks similarly link the Pink Card to investment sentiment. In a 2022 briefing, the Central Africa Policy Centre suggested that predictable accident settlements enhance credit terms for transport firms, allowing them to modernise fleets and comply with emergent environmental standards such as Euro IV emissions limits.

Challenges of Recognition on the Ground

Nonetheless, implementation gaps persist. Some rural insurers still issue obsolete green-colored certificates; roadside agents occasionally confiscate vehicles despite valid Pink Cards; and claims adjustment across borders can run into divergent judicial calendars, currency conversions and language barriers, as detailed in a 2021 report by the African Development Bank.

Legal harmonisation remains a thorny issue. While the CIMA Code provides a common regulatory bedrock, civil procedure varies among member states. Experts advocate bilateral memoranda to accelerate evidence transfer and digital platforms for real-time claim tracking, a model already piloted between Gabon and Equatorial Guinea.

Financing is another hurdle. Reinsurance pools underpinning the scheme require timely premium transfers. Late remittances, sometimes linked to foreign-exchange shortages, can strain trust among national bureaus. The Bank of Central African States is exploring escrow mechanisms to cushion such lags without resorting to punitive interest rates.

Toward Seamless Implementation

Against that backdrop, CEMAC ministers recently approved a phased digitalisation plan. Beginning 2024, every Pink Card will carry a QR code linking to a regional database hosted in Douala. Border officials armed with handheld scanners should be able to authenticate policies within seconds, reducing subjective discretion.

The Republic of Congo has volunteered as an early adopter. Its telecommunications regulator is coordinating with insurers to secure bandwidth along the RN1 corridor toward Cameroon. Officials expect the pilot to dovetail with broader national digital transformation objectives championed by President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s administration.

Stakeholders emphasise that the Pink Card’s credibility will ultimately rest on equitable claims settlements. To that end, the Council of Bureaux plans joint adjuster trainings and peer reviews, echoing best practices from the European Green Card system. A regional dispute board is also under consideration.

For now, Robert André Elenga’s outreach provides the human face of that broader agenda. Each roadside workshop, each corrected misconception, chips away at the bureaucratic haze surrounding the Pink Card. As awareness grows, so too may the freedom of movement that CEMAC leaders envisaged nearly thirty years ago.

Observers view the initiative as a litmus test for wider monetary-union ambitions, from common passports to rail corridors, signaling CEMAC’s gradual shift from vision statements to operational delivery.