International Health Regulations at a Crossroads

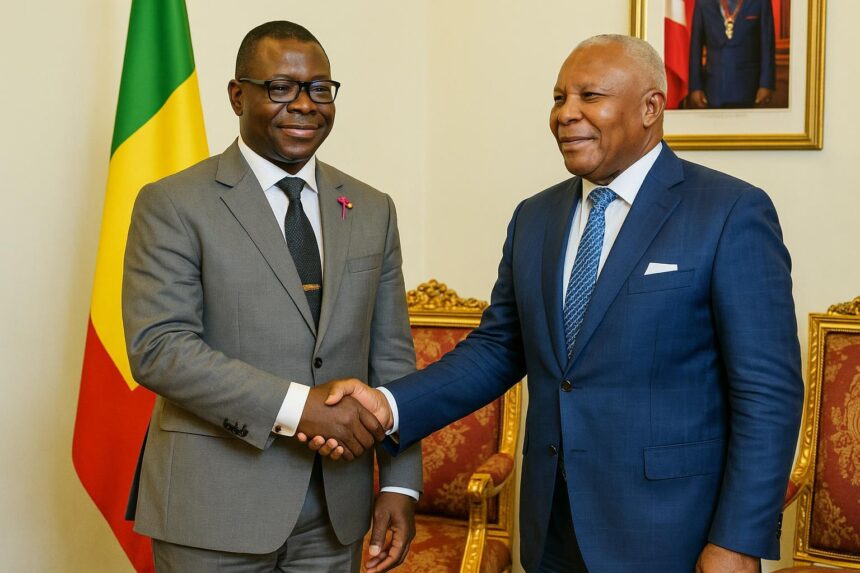

In Brazzaville on 2 October, National Assembly president Isidore Mvouba welcomed Dr Vincent Dossou Sodjinou, WHO Resident Representative, for an update on Congo’s alignment with the International Health Regulations, the legally binding code designed to prevent cross-border disease emergencies.

The discussion came as cholera and mpox clusters reappear along the Congo River while Ebola remains active in neighbouring DRC, underscoring what Dr Sodjinou called “the urgent need for a clear legal backbone that turns good intentions into rapid, coordinated action.”

Fast-Tracking a National Law

At present, Congo applies the 2005 Regulations through ministerial decrees and ad-hoc committees. A dedicated statute, however, would oblige every ministry—from Interior to Livestock—to share data, release contingency funds and clarify field responsibilities before, during and after an outbreak.

“A draft already exists inside the Health Ministry,” the WHO envoy told reporters. “Our teams are refining definitions and penalties so Parliament can debate before the next budget session.” Speaker Mvouba signalled support, noting the lower chamber’s record of adopting health bills by consensus.

Legal scholars at Marien-Ngouabi University believe adoption could make Congo eligible for fresh support under the Pandemic Fund and the African Biosecurity Initiative, two financing platforms that reward states able to prove compliance with the International Health Regulations (Reuters, WHO Africa newsroom).

Primary Health Care Returns to Center Stage

Beyond emergency law, the meeting revived a long-running ambition: restoring robust primary health care in every arrondissement. Many clinics, built in the early 2000s, struggle with staff turnover and supply gaps, pushing patients toward overcrowded referral hospitals.

Dr Sodjinou praised the Assembly’s health committee, chaired by cardiologist Dr Emeline Mbemba, for drafting a roadmap that links rural dispensaries to telemedicine hubs in Brazzaville and Pointe-Noire. “Prevention gets cheaper when the first consultation happens close to home,” he said.

According to the latest Demographic and Health Survey, half of Congolese households live within five kilometres of a primary facility, yet only one in three attend regularly. Cost, transport and stock-outs remain major hurdles—a situation the new plan aims to correct.

Keeping the WHO Africa Hub in Brazzaville

The conversation also touched on an issue dear to national pride: the presence of the WHO Regional Office for Africa, established in Brazzaville since 1956. Rumours of relocation occasionally surface online, but the UN agency has repeatedly dismissed them.

“The headquarters stays here—full stop,” Dr Sodjinou affirmed, citing statements by WHO Director-General Dr Tedros Ghebreyesus and Regional Director Dr Matshidiso Moeti. He thanked the government for upgrading fibre links and security perimeters around the leafy district of Ravin du Rail.

Speaker Mvouba recalled that hosting the regional office has spurred conferences, scholarships and laboratory projects that benefit local youth. For economist Yvonne Kimangou, those spin-offs generate “a silent dividend” worth millions of CFA francs through hotel nights and air traffic.

What Happens Next for Congolese Households

In the coming weeks, a mixed task force will circulate the draft law to civil society, provincial assemblies and professional orders. Stakeholders may send comments by email or through town-hall meetings planned in Dolisie and Owando, according to the parliamentary calendar.

Once the bill reaches the plenary, deputies are expected to fast-track it under the emergency procedure that limits debate to two readings. If passed, the text would grant the Health Minister authority to declare a public health alert and trigger automatic funding.

For families, the practical effect could materialise at border crossings, where trained agents would apply harmonised screening protocols. Traders like Maïssa Kimbembé, who ferries produce between Boma and Brazzaville, hope greater clarity will “reduce waiting times and keep goods fresh.”

In towns along the railroad, renewed primary care may arrive through solar-powered containers staffed by nurse-midwives. Pilot units financed by the World Bank have already cut maternal deaths in Mindouli by 30%, a figure health officials want to replicate nationwide (World Bank data).

Communication will be key. The Assembly plans a short video series explaining how parents can report unusual symptoms via the toll-free 3434 hotline, while influencers on TikTok and Facebook Live will relay preventive tips in Lingala, Kikongo and French.

Above all, the initiative reflects Brazzaville’s determination to safeguard lives while reinforcing its reputation as a regional health capital. “Preparedness is the best insurance we can offer our citizens,” Speaker Mvouba concluded, “and Parliament stands ready to deliver that guarantee.”