Independence Day’s Enduring Promise

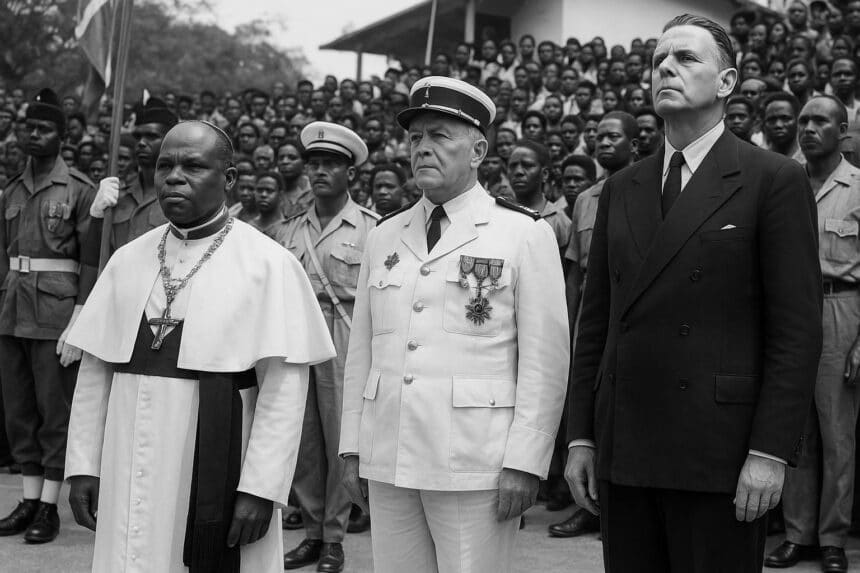

The tricolour was hoisted over Brazzaville on 15 August 1960, marking the Republic of Congo’s accession to sovereignty in parallel with the broader decolonisation wave then sweeping Africa (African Union archives). Hopes ran high that the young nation, rich in forests and navigable rivers, would fashion a modern polity.

The first president, Fulbert Youlou, a charismatic former priest, sought to merge spiritual prestige with political authority. Early diplomatic recognitions were secured in Paris, Washington and Léopoldville, but fiscal constraints and limited export baskets—mainly timber and palm oil—hampered the envisioned social programmes and infrastructure rollout.

Euphoria to the August 1963 Upheaval

Mounting wage arrears, party factionalism and perceptions of regional favouritism ignited the August 1963 demonstrations later dubbed the “Trois Glorieuses”. Trade-union militias joined reform-minded officers, forcing Youlou to resign after only three tempestuous years, illustrating how infant institutions struggled to arbitrate socio-economic grievances in the post-colonial setting.

Ideological Shifts in a Cold War Theatre

The political vacuum ushered in short-lived provisional councils until Captain Marien Ngouabi proclaimed the People’s Republic in December 1969, adopting a Marxist-Leninist orientation aligned with Moscow and Beijing (Archives nationales du Congo). The new charter centralised power and prioritised literacy campaigns while nationalising key forestry concessions.

Seismic surveys off Pointe-Noire meanwhile confirmed commercially viable offshore oil reserves in the early 1970s (TotalEnergies reports). Hydrocarbons soon overtook timber as the primary export, offering fresh fiscal space but also exposing governance structures to volatile price cycles that would intermittently complicate macroeconomic planning.

Ngouabi’s assassination in March 1977 underscored the fragility of ideological consensus. A national committee led briefly by Joachim Yhombi-Opango set the stage for Colonel Denis Sassou Nguesso, whose steady ascent blended military discipline with negotiations inside the ruling Congolese Labour Party, ensuring a more predictable chain of command.

Throughout the late Cold War, Brazzaville cultivated pragmatic links with both Soviet advisers and Western oil companies, leveraging its Atlantic seaboard. The dual outreach, noted by French geopolitical journal Hérodote, helped secure budgetary aid while avoiding the proxy-conflict escalations that ravaged neighbouring states.

The Sassou Nguesso Era and Institutional Continuity

The 1991 National Conference echoed reformist currents sweeping Africa after the Berlin Wall’s fall. Delegates drafted a pluralist constitution and scheduled competitive elections, reflecting internal calls for participatory governance and international encouragement from the European Community and the Organisation of African Unity.

Disputed poll results and rival security detachments plunged the nation into a brief but destructive conflict in 1997, displacing thousands along the Congo River corridor according to United Nations bulletins. Regional mediation led by Gabon facilitated a ceasefire, enabling Sassou Nguesso to re-assume the presidency.

Early 2000s reconstruction combined debt rescheduling under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries framework with public-private partnerships that refurbished rail links and expanded hydrocarbons capacity. The IMF’s 2010 Article IV consultation credited Brazzaville for stabilising inflation while urging diversification toward agriculture and digital services.

Energy Wealth and Development Strategies

Recent national development plans, including the 2022-2026 PND, prioritise special economic zones near Oyo and Pointe-Indienne to attract regional supply chains. Officials cite the African Continental Free Trade Area as a catalyst for processing timber domestically, enhancing value retention and job creation consistent with Agenda 2063 benchmarks.

Diplomatically, Brazzaville often hosts behind-the-scenes negotiation platforms for Central African peace processes, leveraging its image as a neutral convenor. The International Crisis Group notes Congo’s facilitation in talks on the Central African Republic and Chad, bolstering its standing within the Economic Community of Central African States.

Cultivating Governance and Collective Memory

Soft power instruments also contribute. The Pan-African Music Festival, relaunched in 2015, attracts millions via regional broadcasters, while the Denis Sassou Nguesso University in Kintélé collaborates with UNESCO on cultural heritage curricula, projecting an academic footprint beyond traditional diplomatic communiqués.

Governance metrics display incremental progress. The World Bank’s 2023 Doing Business snapshot records faster property registration times, and Brazzaville ratified the African Peer Review Mechanism, committing to periodic assessments. Civil society groups nevertheless emphasise continual vigilance to ensure reforms translate into equitable service delivery.

Commemorations of 15 August blend military parades with school essay competitions, reinforcing a narrative of resilience. Interviews by Les Dépêches de Brazzaville reveal that younger generations increasingly associate the flag not only with anti-colonial struggle but with aspirations for digital connectivity and ecological stewardship.

Prospects for a Diversified Future

Looking ahead, policymakers argue that a diversified, greener economy coupled with sustained regional mediation could anchor Congo as a stabilising hub in Central Africa. The trajectory, observers suggest, will hinge on consolidating institutional capacities cultivated since independence while navigating global energy transitions with strategic foresight.

International investors will watch debt transparency measures and the forthcoming census, both expected to enhance statistical credibility and planning.