Congolese literature and national wounds

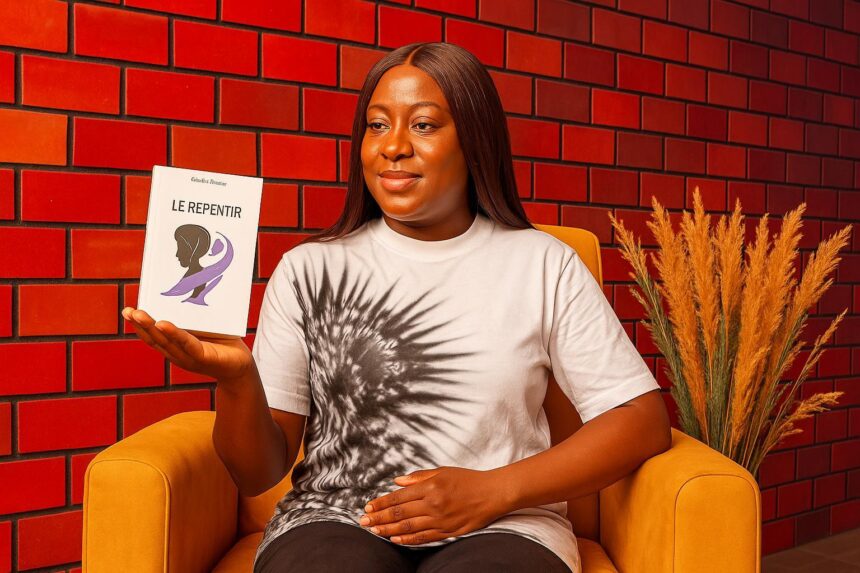

When Congolese writer Ghislain Thierry Maguessa Ebome released “Le Repentir”, many readers outside Brazzaville saw only a tragic love story. Yet diplomats operating in Central Africa quickly recognised a rare laboratory of ideas for post-conflict reconciliation, distilled through the fictional encounter between victim and repentant perpetrator.

Set in the Pool region, the novel follows Sardine, a disillusioned ex-Ninja militiaman, as he seeks forgiveness from the Malonga family after killing their son during the 1998–2003 violence. The plot, inspired by documented militia testimonies collected by Caritas and Justice & Paix, resonates beyond literature.

State-led reconciliation policies

The narrative invites an overdue question: can individual remorse scale up to national healing? Congo-Brazzaville’s authorities think so. In 2001 they instituted the Comité de Paix et de Réparation, channeling community hearings, symbolic reparations, and agricultural cooperatives to reintegrate nearly 30 000 ex-combatants, according to UNDP field briefs.

Officials say the programme has reduced recidivism among former militiamen to under eight percent. Critics counter that figures are difficult to verify. Nonetheless, the World Bank’s 2022 Fragility Assessment cited the Pool as “a zone of cautious stability”, noting improved trade flows along the refurbished National Road 1.

Faith actors and traditional mediators

Faith communities remain crucial. The Episcopal Conference, partnering with the Higher Council of Islamic Affairs, convenes monthly “tables of forgiveness” in Kinkala. Bishop Bienvenu Manamika explained last December that “grace complements justice; without both, ghosts keep visiting the village”. His remarks echo Pope Francis’s 2015 address in Brazzaville.

Traditional mediators, locally called bangangoulou, facilitate the ritual side of reconciliation. They organise palm-wine ceremonies where victims’ relatives publicly break calabashes, symbolising the end of blood debt. Anthropologist Tchicaya U Tam’si argues such gestures provide “social oxygen”, allowing state-led amnesties to embed themselves in daily life.

Stability and economic corridors

Yet realpolitik cannot be ignored. Brazzaville’s leadership sees stability in the Pool as pivotal for the Pointe-Noire-Brazzaville corridor, which transports over 70 percent of national exports. By easing residual militia grievances, the government shields new Chinese-financed rail and fiber-optic projects from sabotage, diplomats privately observe.

International partners tread carefully. The European Union funds psychosocial support through the PARPAF programme but insists on Congolese ownership. “External blueprints rarely survive local realities,” notes Stéphane Giraud of Expertise France, invoking lessons from Sierra Leone’s Truth Commission. The approach aligns with Brazzaville’s preference for sovereignty-respecting cooperation.

Truth-seeking versus imported models

Still, challenges persist. The National Commission on Human Rights recorded 1 200 unresolved disappearance cases linked to the militia era. Families demand truth as well as absolution. Observers argue that a limited, time-bound Truth Forum, possibly chaired by the Economic Community of Central African States, could bridge expectations.

Political analysts caution against importing adversarial models of transitional justice. In interview, Professor Juste-Ive Ibovi stressed that “South Africa’s hearings were televised but our rural bandwidth is human interaction. A megaphone can’t replace a palaver tree.” His comment underscores the need for culturally adapted transparency.

Livelihoods and grassroots vigilance

Economic incentives further shape reconciliation. The state’s Disarmament, Demobilisation and Reintegration scheme now offers micro-grants prioritising cocoa cultivation, responding to UN Food Agency market studies projecting rising demand. By equating peace with livelihoods, Brazzaville seeks to convert former fighters into stakeholders of agrarian diversification away from oil reliance.

Women’s groups, often overlooked, drive grassroots vigilance. The network Femmes Debout trains widows to monitor early-warning indicators, from sudden cattle thefts to inflammatory rumour on local radio. Their alerts feed into the Interior Ministry’s Situation Room, an innovation highlighted in the 2023 African Union Peace Report.

From classrooms to regional doctrine

Literature itself is becoming policy fuel. The Ministry of Culture has commissioned travelling theatre adaptations of “Le Repentir” to tour secondary schools. Teachers report improved class discussions on accountability. A survey by Université Marien Ngouabi found 62 percent of students preferred dialogue-based conflict resolution after viewing the play.

Comparative studies show similar strategies in Rwanda and Liberia reduced relapse into communal violence when coupled with civic education. Congo’s curriculum reform slated for 2025 will integrate modules on restorative justice, according to the Education Ministry. Donors expect this soft-power investment to buttress long-term cohesion.

For now, survivors like Beljamie Malonga embody the quiet progress. “Forgiveness doesn’t erase grief, but it stops it from governing our future,” she told Radio Congo last month. That sentiment, mirrored across village dialogues, suggests that the cycle of retaliation can indeed be interrupted, albeit patiently.

Diplomatic observers view Congo’s evolving ecosystem of pardon as a case study for conflict-affected states seeking locally rooted solutions compatible with sovereign agency. If literature can inspire policy—and policy reinforce literature—the Pool’s painful chapter may yet seed a regional doctrine of pragmatic, durable peace.

Regional organisations are taking note. ECCAS is drafting a handbook labelled “Dialogue First”, basing one chapter on Congo’s village mediations. A diplomat involved says the document, to circulate at the 2024 Libreville summit, could standardise preventive diplomacy tools across Central Africa’s mosaic of lingering post-war grievances.