A Celebrated Voice Falls Silent

News of Déo Namujimbo’s passing swept across literary circles on Monday morning, little more than twelve hours after the prolific Franco-Congolese author succumbed to a long illness in a Paris suburb, according to a family statement shared with Les Echos du Congo-Brazzaville.

Namujimbo, sixty-three, had lived in French exile since 2009, yet he never abandoned the Great Lakes narratives that shaped his youth in Bukavu, South Kivu, turning them into speeches and manuscripts that earned standing ovations from Montreal to Marseille.

Family members have opened a condolence wp-signup.php at their Vigneux-sur-Seine residence, where discrete visitors file through a small garden to sign pages already dense with verses, prayers and simple lines such as, “Your voice still guides our pen.”

An official funeral programme is expected later this week, relatives say, but they indicate the ceremony will respect both Roman Catholic rites and Banyamulenge traditions, reflecting the writer’s insistence on celebrating every strand of his multicultural identity.

From Bukavu to Paris, an Itinerant Pen

Born in 1960 beside Lake Kivu, Namujimbo experienced Congo’s post-independence turbulence first-hand; gunfire, he once said during a Geneva lecture, replaced crickets as the soundtrack of his evenings.

That childhood imagery fuelled early poetry journals circulated through Bukavu schools and later matured into novels, short stories and monologues delivered on African diaspora stages.

Critics frequently compared his clipped yet musical prose to that of Sony Labou Tansi, another Congolese icon, although Namujimbo politely brushed away comparisons, insisting every conflict carves out its own syntax.

Last Work Exposes East Congo Turmoil

His final major publication, La Grande Manipulation de Paul Kagame, co-authored with veteran journalist Françoise Germain-Robin and released by Arcanes 17 last spring, spans 365 pages of investigative reportage and personal memoir.

The book retraces three decades of armed upheaval in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, arguing that unresolved grievances from the 1994 Rwanda genocide continue to spill across porous borders and into remote villages.

Namujimbo and Germain-Robin describe an “empire of silence”, echoing Belgian filmmaker Thierry Michel’s recent documentary and Nobel laureate Denis Mukwege’s appeals for an international tribunal to prosecute war crimes.

While the book devotes several chapters to the M23 rebellion and Kinshasa’s military response, it equally criticises what the authors call the world’s “strategic indifference”, a phrase that drew packed auditoriums during their European launch tour.

Rwandan officials denied the allegations outlined in the volume, branding them “speculative”, yet regional analysts interviewed by France 24 conceded the narrative captured local frustrations often missed by swift diplomatic communiqués.

Regional Reactions and Diplomatic Echoes

In Congo-Brazzaville, cultural groups have stressed the importance of Namujimbo’s cross-border outlook, noting that his writings encourage Central African youth to approach conflict with critical empathy rather than inherited grievance.

Alphonse Nzoungou, a literature lecturer at Marien Ngouabi University, said by phone, “He opened a window between our two Congos; young authors here study his pacing to understand how personal stories can illuminate bigger crises.”

Beyond the academy, diaspora associations have launched online readings, posting rare audio of Namujimbo’s baritone delivering passages that blend Swahili lullabies with Parisian street slang.

Bookstores in Brazzaville, Pointe-Noire and Kigali have reported a spike in demand for his entire catalogue, a phenomenon distributor Livre-Plus attributes to “readers wanting to keep a tangible part of him at home”.

According to medical staff cited by relatives, the author’s health declined over several months, yet he continued to edit drafts from his hospital bed, dictating revisions to a nephew who doubled as research assistant.

Friends say the unfinished manuscript, rumoured to explore post-colonial city planning in Central Africa, could be completed by colleagues with whom he shared cloud files.

Legacy for Congo-Brazzaville’s Youth

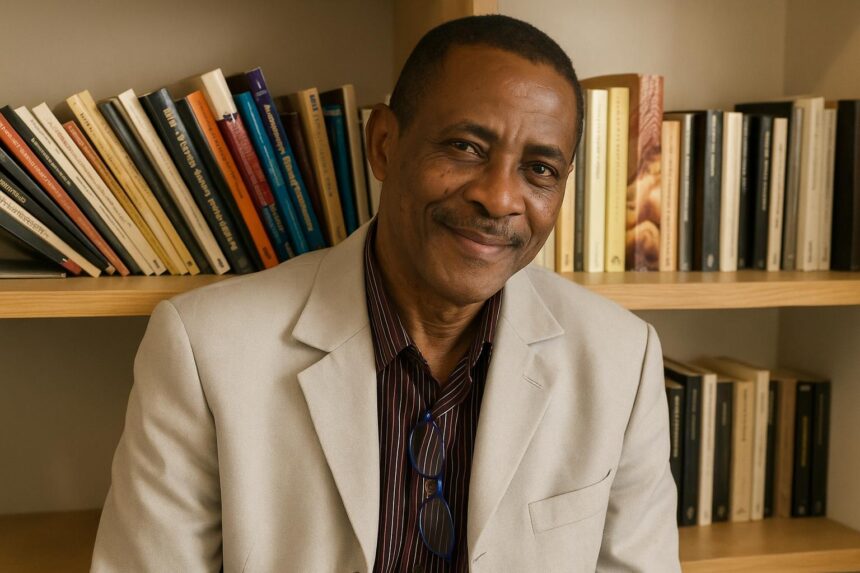

For now, though, attention turns to Vigneux-sur-Seine, where candles flicker beside a framed photograph of Namujimbo smiling under a felt hat, reminding mourners that the man who chronicled conflict also cherished simple style.

As messages pour in from presidents, poets and former students, one line recurs: despite distance, Déo Namujimbo made every audience feel that the Great Lakes story was theirs to write next.

Pierre Mumbere, who organised Namujimbo’s first book tour in Lyon in 2010, remembers a restless thinker: “Even over coffee he asked waiters about their hometowns, mining small tales for universal emotion.” That curiosity, Mumbere argues, explains why translations exist today in Spanish, Arabic and Lingala.

Publishers confirm a commemorative boxed set will arrive before Christmas, ensuring libraries from Brazzaville to Boston can shelve his oeuvre together. Until then, readers keep refreshing social feeds, waiting for the funeral date that will close a chapter but not the conversation.

For young writers in the Republic of Congo, Namujimbo’s journey offers a template that blends civic courage with artistic discipline. Literary blogger Christelle Oba notes that his balanced critique of regional actors demonstrates how to document suffering without surrendering hope, a lesson classrooms will revisit for years.