Night-time touchdown in Maya-Maya

The Falcon 900 bearing former Guinea-Bissau president Umaro Sissoco Embaló rolled to a halt on Brazzaville’s Maya-Maya runway shortly after 01:00 Saturday, officials confirmed. The discreet arrival ends a frenetic two-day journey triggered by the coup that upended power in Bissau on 27 November.

- Night-time touchdown in Maya-Maya

- A swift exit from Senegalese stopover

- Brazzaville, a familiar and trusted haven

- A long-standing bond with Sassou-Nguesso

- Calm reception in the Congolese capital

- Online pride and past precedents

- Regional diplomacy gears up

- What next for Guinea-Bissau?

- Hospitality diplomacy in Central Africa

A source inside Congo-Brazzaville’s presidency told us that the aircraft, chartered by the Congolese state, taxied directly to a private hangar where the visitor and roughly a dozen aides were met by protocol officers before being transferred to a riverside hotel under light security.

A swift exit from Senegalese stopover

Earlier on Thursday night Embaló had surfaced in Dakar, a city where he owns a home, after crossing regional airspace with provisional clearances. His entourage insisted Senegal was only a ‘technical pause’ yet the sighting quickly ricocheted through social networks across West Africa.

Senegal’s prime minister Ousmane Sonko, addressing lawmakers on Friday, criticised what he called “a backstage arrangement” around the Bissau vote, comments understood by diplomats to be aimed at Embaló. Observers in Dakar believe the statement accelerated the former leader’s decision to board the Congo-bound jet.

Brazzaville, a familiar and trusted haven

For many in Brazzaville the arrival felt almost routine. Embaló has visited at least six times since 2020, regularly staying in the northern town of Oyo, birthplace of President Denis Sassou-Nguesso, to fish on the Alima River or discuss regional security over palm wine.

This familiarity, say presidential aides, explains why Brazzaville responded within hours to his request for logistical assistance once the putschists seized Bissau’s radio tower. “He trusts the Congolese leadership and we value dialogue,” a senior official noted, asking not to be named.

A long-standing bond with Sassou-Nguesso

Sassou-Nguesso and Embaló cultivated their rapport during ECCAS and ECOWAS summits, often portraying themselves as pragmatic bridge-builders between Central and West Africa. In October the Guinean-Bissau leader spent a weekend in Oyo discussing energy links and forest protection projects championed by the Congo-Basin Climate Commission.

Sources close to both men say Embaló phoned Sassou-Nguesso roughly one hour after the first gunfire in Bissau. The call, characterised as ‘frank and emotional’, allowed the Congolese side to alert partners and prepare diplomatic channels while keeping a strictly neutral stance publicly.

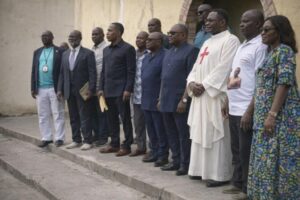

Calm reception in the Congolese capital

In Brazzaville the atmosphere around Embaló’s hotel on the corniche remained calm this Saturday. Patrons snapped quick selfies but police gently ushered them away. No official programme has been released; aides say the visitor intends to “rest and reflect” before deciding on longer-term arrangements.

In the early hours, the Congolese Red Cross dispatched an ambulance as a precaution, though medical staff reported no health issues. Such gestures, small yet symbolic, reinforce Brazzaville’s bid to brand itself as a humanitarian hub alongside its more discreet diplomatic overtures.

Online pride and past precedents

Congolese social media, meanwhile, pulsed with speculation yet also with pride at the country’s reputation for quiet mediation. Commenters recalled that former Central African leaders Michel Djotodia and François Bozizé both transited through Brazzaville at delicate moments, reinforcing the capital’s image as a regional conflict de-compressor.

Regional diplomacy gears up

Beyond Congo’s borders the incident stirs fresh debate on constitutional stability in West Africa. ECOWAS, whose last summit Embaló chaired, has yet to recognise the coup leaders. Diplomatic sources in Abuja hint at emergency consultations, with Brazzaville expected to share insights gleaned from its high-profile guest.

In Paris and Lisbon, home to large Bissau-Guinean communities, foreign ministries called for “respect of democratic institutions” while avoiding direct condemnation. Analysts such as Djibril Baldé of the Institute for Security Studies say the presence of Embaló in Congo may offer “breathing space” to negotiate without further violence.

What next for Guinea-Bissau?

Back in Bissau, radio stations run intermittent music loops as soldiers patrol key junctions. The self-declared National Stabilisation Council has promised elections within nine months. Yet civil society groups fear economic paralysis: banks remain closed, and cashew exporters warn a prolonged shutdown could dent seasonal incomes.

For now Embaló refrains from public statements, mindful that any tough rhetoric could harden positions at home. One aide summed up his mood: “He feels relief, exhaustion and a responsibility to avoid bloodshed.” The coming days may test that resolve as rival factions jockey for recognition.

Hospitality diplomacy in Central Africa

Brazzaville’s role as an occasional sanctuary underscores a wider tradition in Central Africa, where hosting embattled leaders can lower the temperature of crises while projecting soft power. Professor Liliane Mapata of Marien Ngouabi University calls it “hospitality diplomacy”, a tool that lets Congo punch above its demographic weight.

Whether Embaló’s stay lasts days or months, his presence already weaves Congo-Brazzaville into the search for a peaceful outcome in Guinea-Bissau. For ordinary Congolese, the immediate concern remains practical: traffic diversions around the hotel and the hope that their capital once again helps avert wider unrest.