A renewed call from Brazzaville’s Senate floor

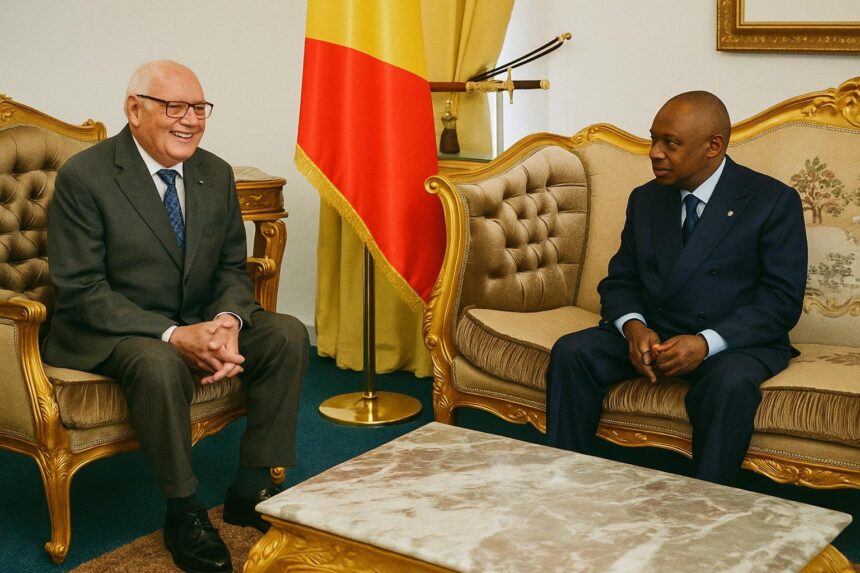

The marble corridors of the Congolese Senate briefly echoed French municipal experience on 17 July, when Jean Girardon, Mayor of Mont-Saint-Vincent and scholar at the Sorbonne, held court with Speaker Pierre Ngolo. Emerging from the meeting, Girardon distilled four decades of local governance into a single axiom: competencies without corresponding resources breed public frustration rather than administrative vitality. His remark, while ostensibly elementary, touches the core of Congo-Brazzaville’s decentralisation project initiated under President Denis Sassou Nguesso in the early 2000s and reaffirmed in the National Development Plan 2022-2026.

- A renewed call from Brazzaville’s Senate floor

- Historical trajectory of Congolese decentralisation

- Fiscal autonomy: the indispensable missing link

- Strengthening human capital for local governance

- Multi-level governance and sectoral synergies

- International benchmarking and measured optimism

- An agenda aligned with national stability

- Outlook: from discourse to disbursement

Historical trajectory of Congolese decentralisation

Legislative cornerstones such as Law n°3-2003 on administrative organisation and subsequent fiscal statutes in 2011 established communes, urban districts and départements as autonomous legal persons. In practice, however, the Treasury in Brazzaville has retained predominant leverage, with local budgets still accounting for barely eight per cent of public expenditure according to the World Bank’s 2023 governance update. Central authorities argue that gradualism safeguards macro-economic stability, yet local executives contend that limited fiscal room curtails the very democratic participation the reforms were designed to enhance.

Fiscal autonomy: the indispensable missing link

At the heart of the current debate lies a quantitative dilemma. National statutes transferred responsibility for primary health posts, feeder roads and basic education to communes, but the average transfer per inhabitant remains below the regional mean in Central Africa (African Development Bank 2022). Girardon’s Brazzaville intervention thus resonates with domestic voices calling for an expanded Equalisation Fund, scheduled for parliamentary review later this year. Government insiders indicate that the Ministry of Finance is exploring a formula tying transfers to local revenue-effort indicators, a design intended both to reward good governance and to protect poorer jurisdictions.

Beyond transfers, fiscal autonomy implies the power to raise revenue. The General Tax Code already lists a modest palette of local levies—market fees, property taxes and small-business licences—but collection rates seldom exceed forty per cent. Digital cadastre pilots in Pointe-Noire and Dolisie, supported by UN-Habitat, have reportedly doubled property tax yields within two fiscal years, suggesting a pathway to self-sustaining communes if scaled nationwide.

Strengthening human capital for local governance

Resources include not only francs CFA but also managerial skills. The Senate workshop in which Girardon participated belongs to a broader capacity-building arc that has seen over 600 councillors trained since 2021 under the Programme d’Appui à la Décentralisation Financée. International partners underscore that locally elected officials frequently juggle administrative duties with private employment, prompting debate on professionalising municipal offices. A draft statute currently circulating would introduce graded indemnities and mandatory ethics training, aligning Congo’s framework with African Union guidelines on decentralisation (AU 2019).

Multi-level governance and sectoral synergies

Fiscal equations aside, efficiency hinges on clear vertical coordination. Tourism, cited by Girardon, illustrates the point: coastal communes manage beach infrastructure, while départements oversee heritage promotion. The Ministry of Tourism is therefore piloting inter-communal syndicates designed to pool marketing budgets and harmonise regulations. Similar logic informs the Integrated Agricultural Zones established in Cuvette-Ouest, where communal agronomists now report to a département steering committee. Early evaluations by the Food and Agriculture Organization observe shorter procurement cycles and higher smallholder participation.

International benchmarking and measured optimism

Congo-Brazzaville’s openness to comparative learning has grown markedly. Delegations recently observed Morocco’s Régions pilot and Rwanda’s performance-based grants, experiences that Brazzaville’s policymakers deem instructive yet not prescriptive. The government’s 2023 White Paper acknowledges diversity of context while committing to adopt a medium-term expenditure framework for local governments by 2025, a timeline seen by diplomats as ambitious but feasible provided hydrocarbon revenues stabilise.

In that sense, Girardon’s exhortation is less a reproach than a strategic reminder: competitive federalism is emerging across the continent, and nations that fail to empower their municipalities risk foregoing inclusive growth and, by extension, the soft power dividends of demonstrable democratic practice.

An agenda aligned with national stability

The presidency maintains that methodical decentralisation complements, rather than challenges, the state’s cohesion objectives. Government communiqués routinely frame local empowerment as a pillar of national unity, a stance echoed by the ruling Congolese Labour Party in recent policy briefs. By channeling additional resources to communes while tightening accountability standards, Brazzaville seeks a virtuous circle in which fiscal credibility at the local level reinforces investor confidence country-wide.

Outlook: from discourse to disbursement

Diplomatic observers in Brazzaville detect a rare consensus: the decentralisation train has left the station, and its next stop demands tangible funding. Should the forthcoming finance bill substantively augment the Equalisation Fund and enact the new local-elected statute, Congo-Brazzaville could reposition itself as a regional case study in balanced statecraft. The ensuing months will therefore test the political resolve to translate the Senate’s eloquent exchanges into budgetary realities capable of shaping lives far from the capital’s banks of the Congo River.