Brazzaville’s Strategic Moment in Multilateral Health

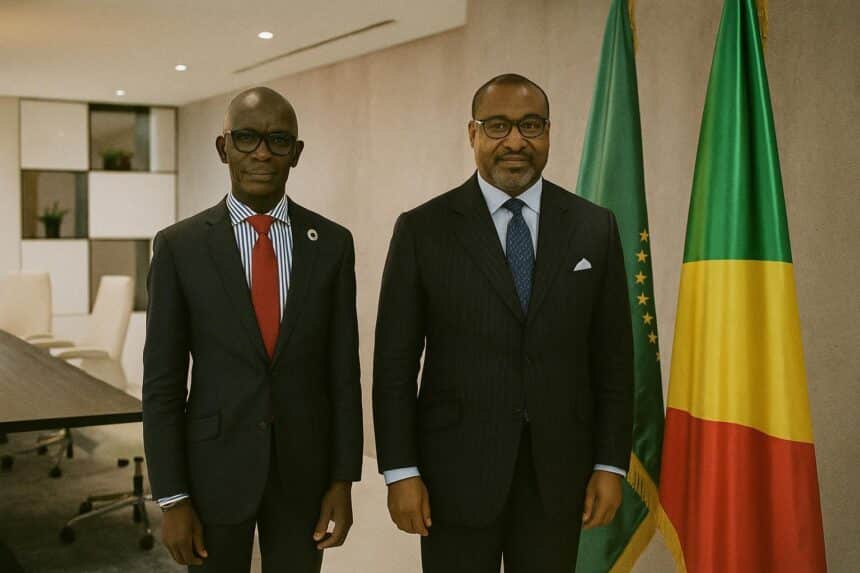

Barely two kilometers from the Congo River’s languid bends, a corridor of palm trees leads to the World Health Organization’s African Regional Office, a diplomatic presence that has shaped the city’s identity since 1974. When Regional Director Professor Mohamed Yakub Janabi met Minister of International Cooperation Denis Christel Sassou Nguesso on 21 July, the discussion transcended protocol: both interlocutors agreed to convene, in the coming weeks, a joint Congo-WHO commission intended to refine the instruments of collaboration in public health. The move follows a pattern in which Brazzaville has consistently leveraged health diplomacy as a vector for soft power and continental leadership (WHO, 2023).

Primary Care as Geopolitical Capital

The agenda foreshadowed for the commission reads less like a technical annex and more like a blueprint for regional health security. By prioritising primary health care, the Congo signals its alignment with the Astana Declaration and gently reminds partners that universal health coverage is an attainable horizon. Diplomats in the corridors of the African Union note that Congo’s enrolment of community health workers—over 12 000 according to the Ministry of Health—confers political legitimacy at home while offering a replicable model for neighbouring states grappling with post-pandemic fatigue.

Professor Janabi’s emphasis on primary care resonates with new WHO metrics indicating that every US dollar invested in that level of the health system generates an estimated return of nine dollars in economic growth over a decade (WHO Economic Case for PHC, 2022). For policy makers in Brazzaville, those figures reinforce an argument long advanced by President Denis Sassou Nguesso: robust health structures are prerequisite to diversification of the hydrocarbon-dominated economy.

Medical Education and Human Capital Formation

Another axis of deliberation concerns medical training. The country’s Félix Houphouët-Boigny University of Health Sciences, funded through a mix of national allocations and concessional loans from the African Development Bank, graduates roughly 250 physicians annually. Yet the sub-Saharan benchmark, the WHO reminds, should approach 4.45 health workers per 1000 inhabitants. The commission is expected to explore twinning arrangements with teaching hospitals in Nairobi and Rabat, as well as digital curricula supported by the WHO Academy in Lyon.

Congo’s authorities are equally keen to harness south-south cooperation. Kinshasa’s Institute of Tropical Medicine has informally offered field placements in vector-borne disease surveillance, a synergy that could be formalised under the joint commission’s remit. Such overtures illustrate how the conversation is shifting from unilateral aid to reciprocal capacity building.

Land, Legacy and the Symbolism of Place

Beyond programmatic questions, the talks addressed the valorisation of a parcel of land granted by the Congolese government to the WHO. Situated in the burgeoning administrative district of Kintélé, the site is eyed for a Centre of Excellence on Epidemic Intelligence. Diplomats describe the gesture as both pragmatic and symbolic: by allocating real estate, Brazzaville anchors the WHO presence physically and politically, countering sporadic rumours of relocation to East Africa.

Professor Janabi made a pointed declaration that the regional office ‘will remain in Brazzaville under my mandate’, an assurance welcomed by local staff and by foreign missions that have calibrated their health portfolios around the office’s proximity.

Dispelling Relocation Rumours with Diplomatic Poise

Speculation earlier this year, circulated largely on social media, suggested that the regional office might migrate closer to Africa’s major air hubs. Analysts attribute the chatter to a misreading of WHO’s internal review on office rationalisation. By confronting the narrative directly, both the Congolese government and the WHO reinforced a perception of institutional stability—an asset when courting donors who prioritise predictability. Paris-based health economist Dr. Élodie Bernard observes that ‘continuity of location is often underestimated, yet it undergirds staff retention and supply-chain logistics alike.’

Prospects for Converging Strategic Interests

For Congo, the joint commission offers more than technical dividends. It provides an opportunity to showcase itself as a convening hub at a time when multilateral institutions are recalibrating towards the Global South. The upcoming African Climate Summit in Nairobi has placed health-climate intersections on the diplomatic agenda; Brazzaville’s early partnership with WHO on climate-sensitive diseases could yield negotiating leverage in that forum.

Conversely, the WHO stands to benefit from Congo’s political will and comparatively stable security environment. In the volatile Great Lakes region, the ability to stage rapid deployments from a safe capital is not trivial. The interlocking interests anchor a partnership that appears poised to mature from project-based assistance into a strategic alliance.

While the precise date of the commission remains confidential, sources close to the planning process suggest late August as the most likely window. Should that timeline hold, diplomats and health experts alike anticipate a communiqué articulating measurable targets—for example, increasing immunisation coverage to 92 percent by 2025 and reducing maternal mortality by a third within the same horizon.

Whatever the metrics finally adopted, the forthcoming session underscores a simple truth of twenty-first-century diplomacy: health is no longer an auxiliary portfolio but a central pillar of national projection. In reaffirming its partnership with the WHO, Brazzaville is not merely stewarding public welfare; it is shaping its geopolitical narrative for a region in flux.