What happened at the Congo Embassy in Paris

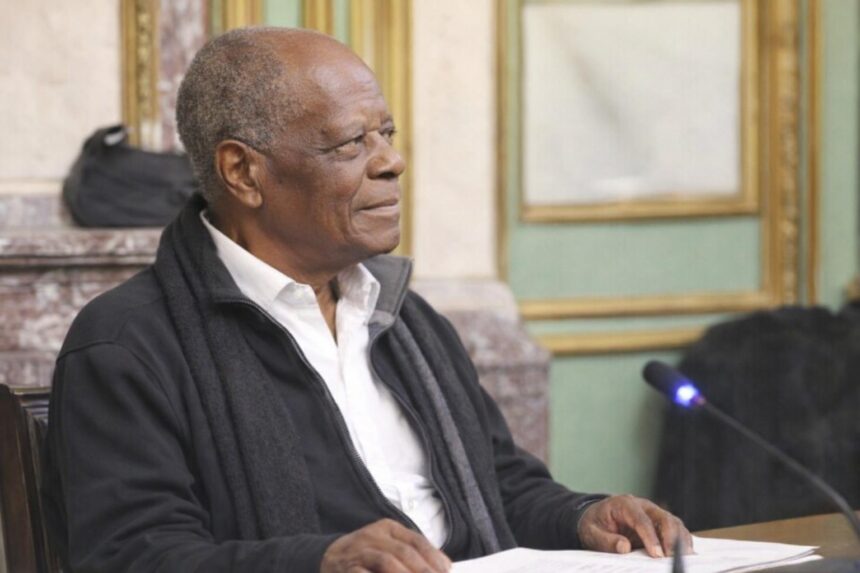

Congolese writer Henri Djombo met readers in Paris for a presentation and signing of his new novel, “Une semaine au Kinango.” The event was moderated by Rudy Malonga and brought together book lovers for an evening centered on fiction, society and the shared pleasure of reading.

- What happened at the Congo Embassy in Paris

- A cultural moment for Congolese readers in France

- “Une semaine au Kinango”: a short timeframe, deep questions

- A subtle social lens, anchored in African realities

- The magnan ants scene and its meaning in the story

- Ecology, unity and the warning at the heart of the allegory

- An ending shaped by hope and rebuilding

- Questions, answers and a long signing line

Held on Saturday 17 January, the gathering filled the Green Room at the Embassy of the Republic of Congo in Paris. The atmosphere was both celebratory and attentive, with many attendees coming to hear how the story was built and what questions it raises about today’s social dynamics.

A cultural moment for Congolese readers in France

Ambassador Rodolphe Adada welcomed the audience and highlighted the strong turnout, reading it as a sign of cultural connection among Congolese living in France. The full room, he suggested, reflected a living bond maintained through literature, public conversation and collective pride in national creativity.

Many familiar figures from literary and intellectual circles were present, adding to the sense of a special occasion. Among the guests mentioned were Professor André-Patient Bokiba, Eric Dibas-Franck, Driss Senda, Emmanuel Dongala, Sami Tchak, Patrice Yengo and Nicolas Martin-Granel.

Also in attendance were Jean-Aimé Dibakana, Marien Fauney Ngombé, Gabriel Kinsa, Inès Féviliyé, Russel Morley Moussala and Criss Niangouna, who delivered an excerpt from the book. Simone Bernard-Dupré, responsible for the novel’s literary critique, guided part of the discussion.

“Une semaine au Kinango”: a short timeframe, deep questions

Simone Bernard-Dupré explained that the novel is built on a tight timeframe: one week. That short span, she argued, pushes readers to pay attention to ordinary events, the kind that can seem minor at first yet reveal social fragilities, power relations, and the weight of individual and collective responsibility.

In her reading, Henri Djombo continues an intellectual approach in which fiction becomes a tool for reflection. The writing aims to remain accessible while still dense enough to invite interpretation, linking personal trajectories to broader questions on contemporary African societies and the pressures shaping them.

A subtle social lens, anchored in African realities

For Bernard-Dupré, the author’s strength lies in blending literary narrative with social observation. She described a style that probes societies and consciences without heavy-handedness, through carefully chosen scenes and an attention to the realities and dilemmas that many readers recognize across African contexts.

During her comments, she evoked a line attributed to Shakespeare—“What a terrible era where idiots lead the blind”—to underline the book’s critical energy. Presented as a literary echo rather than a direct political statement, the quote served to frame the novel’s moral tension.

The magnan ants scene and its meaning in the story

The novel opens with an invasion of magnan ants. Bernard-Dupré noted that magnan ants exist in reality: warrior-like, predatory ants found in the lush forests of the Congo and the Amazon. Carnivorous, they can overwhelm what lies in their path, triggering panic among humans.

In Djombo’s fiction, the ants invade the country’s main prison, described as an institution inherited from the colonial era. The detainees, terrified, rush out, and the prison is left empty of its captives—30,000 people, according to the account shared during the presentation.

To understand the phenomenon, the story consults forces from across Africa and the wider world. Initiates from secret societies gather—mediums, marabouts, magicians, palm readers, sorcerers and miracle workers—arriving to debate how serious the situation is and what response is possible.

Ecology, unity and the warning at the heart of the allegory

The initiates reach a stark conclusion: people must stop altering the environment. The imbalance, they say, could lead to the end of the human species. The narrative also points to a second lesson: a lack of unity among the forces fighting the ants helps the insects win the war.

Bernard-Dupré presented the book as a powerful allegory and a space for deep reflection on the human condition and the path of African countries. The story’s warning about ecological disruption is paired with a broader meditation on responsibility, coordination and the cost of division.

An ending shaped by hope and rebuilding

Despite its severity, the novel’s ending was described as opening onto “combative optimism.” Kinango rebuilds on new foundations: the fight against impunity, economic sovereignty, and the pan-African dream of a united and prosperous Africa—ideas that, in the critic’s view, give the narrative forward movement.

In Bernard-Dupré’s phrasing, Kinango embodies dynamic transformations in Africa and the world. The point is not to offer a simplistic solution, but to show that even after rupture and fear, communities can attempt renewal—through principles, shared goals, and a refusal to surrender to fatalism.

Questions, answers and a long signing line

Henri Djombo then took part in a question-and-answer session. He recalled that Kinango is meant first of all as a mirror of human societies, crossed by tensions and misunderstandings, yet still capable of dialogue. Readers asked about symbols, characters and the novel’s social resonance.

The evening ended with a signing session, with attendees waiting to have their copies dedicated. For many, it was also a chance to exchange a few personal words with the author, turning a formal embassy event into a warm encounter between a book and its public.