Diplomatic Reverberations of a Liturgical Milestone

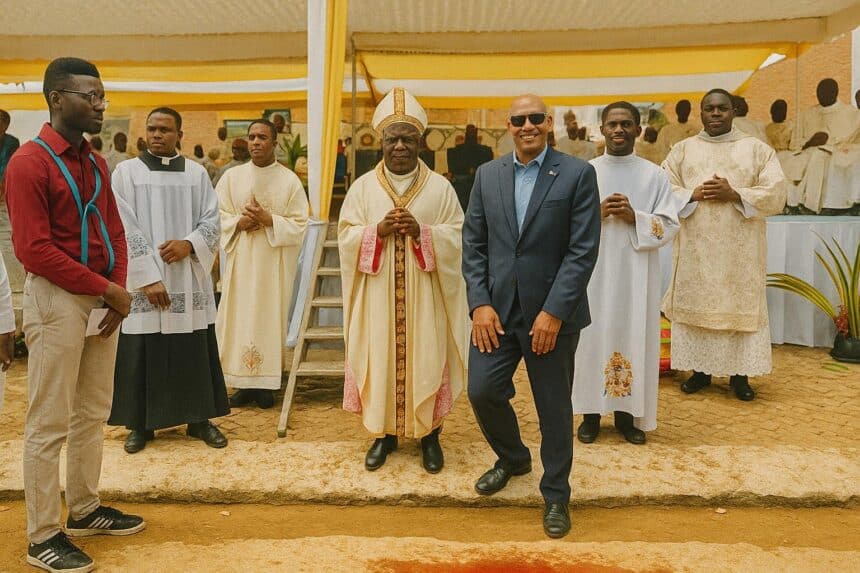

The episcopal consecration that filled the cathedral of Ouesso with incense and polyphonic chants on 21 April was more than an internal Church affair. Presided over by Apostolic Nuncio Javier Herrera Corona, the ceremony drew cabinet ministers, regional governors and representatives from Kinshasa and Libreville, signalling the resonance that a seemingly local liturgical act can acquire in Central African diplomacy. In attendance, the delegation of Catholic Relief Services (CRS) used the solemn occasion to reaffirm a partnership with both ecclesiastical and civil authorities that has matured quietly since the agency opened its Brazzaville office three decades ago.

While the homily emphasised pastoral service, the choreography of official handshakes that followed underscored the political sub-text: in Congo-Brazzaville the Catholic Church remains a respected intermediary between society and state. By taking a front-row seat, CRS positioned itself as a facilitator of that interface, echoing the Holy See’s own tradition of deploying soft power through ritual visibility (Vatican Statistical Yearbook, 2023).

Faith-Based Actors as Vectors of Soft Power

CRS’s symbolic gift of laptops and printers to the new bishop may appear modest, yet within Church structures such tools translate into tangible administrative autonomy. In fragile dioceses such as Ouesso, where forest tracks often stand in for highways, digital capacity can accelerate pastoral logistics, census of the faithful and coordination of social projects. For the host government, outside investment in institutional efficiency is welcome, provided it respects national sovereignty—a balance that the agency has maintained, according to observers from the Congolese Episcopal Conference (La Semaine Africaine, May 2024).

From a geopolitical angle, the gesture embodies a calibrated exercise in soft power. By equipping a local moral authority, CRS enhances its own credibility, securing community entry points that conventional state-to-state diplomacy sometimes struggles to reach. Such influence remains consistent with President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s stated preference for ‘partnerships that elevate local leadership’ expressed during his recent address to faith-based organisations in Brazzaville.

Aligning Pastoral Needs with Development Agendas

The Congolese Church operates more than one-third of the country’s health posts and an estimated 40 percent of primary schools (Ministry of Social Affairs, 2022). Strengthening diocesan governance therefore aligns neatly with international development benchmarks. CRS Country Representative Gabriel M. Yenga confirmed in Ouesso that the agency views pastoral and developmental mandates as mutually reinforcing: ‘An efficient chancery can expedite the distribution of antimalarial commodities as swiftly as it processes sacramental records,’ he remarked in an aside to diplomats.

Such remarks reflect a broader evolution in aid architecture where spiritual capital is increasingly recognised as a driver of social resilience. The Sustainable Development Goals acknowledge in their preamble the contribution of ‘all stakeholders’—language that practitioners on the ground translate into pragmatic alliances. In northern Congo, where riverine isolation complicates the deployment of state personnel, leveraging the Church’s dense parish network offers a cost-effective conduit for aid.

Health Diplomacy in the Sangha Department

On the sidelines of the ordination, CRS officials met Prefect Jules Aimé Ngouaniba to discuss the forthcoming distribution of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets, or LLINs, scheduled before the first rains of June. The campaign, financed by the Global Fund and implemented in coordination with the Ministry of Health, aims to reach 180,000 households across the Sangha. Malaria still claims just under four percent of Congolese GDP through lost productivity (World Malaria Report, 2023), a statistic that lends urgency to preventive diplomacy.

Local authorities voiced appreciation for CRS’s logistical acumen—particularly its capacity to mobilise parish youth groups as last-mile volunteers. By aligning the campaign calendar with the diocesan liturgical cycle, planners hope to transform catechetical gatherings into health-promotion platforms, thereby maximising turnout. The approach resonates with regional strategies endorsed by the African Union’s Centre for Disease Control, which champion community-anchored vector control in forested zones.

Converging Pathways Toward Sustainable Human Security

The Ouesso episode, when viewed through a wider lens, encapsulates the layered tapestry of contemporary statecraft in Central Africa. Ritual prestige, humanitarian pragmatism and political calculus coalesce to produce a governance model in which non-state actors complement but do not supplant governmental stewardship. Brazzaville’s openness to such synergy reflects a confidence in its institutional framework, while CRS’s discreet diplomacy illustrates how external partners can support national agendas without eclipsing them.

Looking ahead, both the Sangha Prefecture and the new episcopal leadership signal readiness to embed development programming into parish action plans, an evolution that may redefine the metrics used by donors to assess impact. Whether measured in reduced malaria incidence or enhanced administrative transparency, the ultimate beneficiaries remain the rural households whose expectations of both Church and State converge around the simple hope for dignified livelihoods. The incense of Ouesso may have dispersed, yet the pragmatic solidarity it symbolised continues to waft through the corridors of policy planning in Brazzaville.