Continental vigilance on Libyan flashpoints

A decade after the collapse of Libya’s central authority, the African Union’s Peace and Security Council once again confronted the familiar specter of urban firefights and humanitarian strain. Meeting by videoconference under Ugandan chairmanship on 24 July 2025, the Council heard field reports describing mortar exchanges between the Forty-Fourth Infantry Brigade and Stability Support Units in southern Tripoli. The recurrent clashes, noted the Council, have idled airports, displaced neighbourhoods and complicated the already fragile ceasefire regime monitored by the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL report, June 2025).

- Continental vigilance on Libyan flashpoints

- Sassou N’Guesso’s committee: diplomacy by persistence

- The elusive ceasefire and Tripoli’s urban fault lines

- Addis-Ababa charter: architecture of a Libyan compact

- Regional stakes: Sahel security and energy corridors

- International coordination remains fragmented

- Prospects for cautious optimism

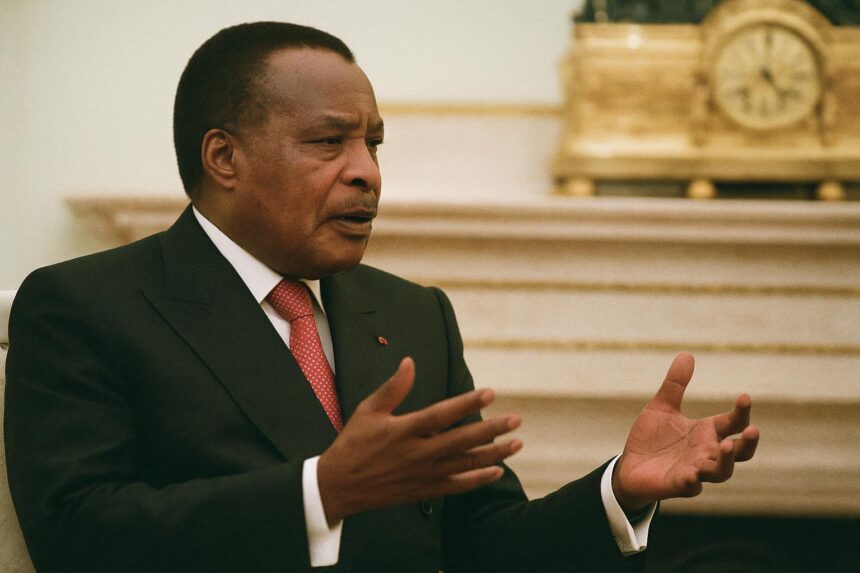

Sassou N’Guesso’s committee: diplomacy by persistence

Presiding from Brazzaville, President Denis Sassou N’Guesso reminded delegates of the mandate he holds as chair of the African Union High-Level Committee on Libya, an organ created in 2011 to provide a distinctly African mediation track. He argued that continental ownership of the dossier remains indispensable, asserting that “no durable settlement can ignore the voices of Africa, the principal stakeholder in the stability of its northern flank” (African Union communiqué, 24 July 2025). Observers within Addis-Ababa headquarters credit the Congolese leader with maintaining institutional memory as global attention has oscillated between counter-terrorism in the Sahel and energy supply routes across the Mediterranean.

The elusive ceasefire and Tripoli’s urban fault lines

The ceasefire inked in Geneva in October 2020 has reduced front-line artillery exchanges, yet intra-militia rivalries inside Tripoli have acquired a transactional, almost commercial logic. Armed groups compete for customs revenue at Mitiga airport and for contracts to guard ministries. Such micro-economies of violence explain the sudden May 2025 confrontation that pitted the Forty-Fourth Brigade against Stability Support Units, leaving at least sixteen civilians dead according to the Libyan Red Crescent. Uganda’s President Yoweri Museveni voiced “profound concern” that these incidents erode public support for national elections already postponed twice (International Crisis Group briefing, July 2025).

Addis-Ababa charter: architecture of a Libyan compact

In this turbulent context, the High-Level Committee has shepherded an inter-Libyan reconciliation charter slated for signing in Addis-Ababa later this year. Draft articles obtained by regional diplomats outline mechanisms for cantonment of heavy weapons, a framework for revenue-sharing from hydrocarbon exports and a sequencing of constitutional referendum before general elections. President Sassou N’Guesso portrayed the blueprint as “a confidence-building instrument forged through compromise rather than imposition.” His emphasis on consensual drafting resonates with the African Union’s doctrine of subsidiarity, whereby continental bodies complement, rather than duplicate, UN mediation (UN–AU Framework Agreement, 2017).

Regional stakes: Sahel security and energy corridors

Neighbouring states follow Libya’s trajectory with a mixture of anxiety and economic calculation. The smuggling routes that traverse Fezzan toward Niger and Chad double as arteries for extremist groups affiliated with Islamic State in the Greater Sahara. A relapse into nationwide conflict would reverberate across the Sahel, undermining recent gains by the Multinational Joint Task Force along the Lake Chad basin. Simultaneously, European gas buyers—still adjusting supply chains after the Ukraine crisis—view Libya’s 1930-kilometre Greenstream pipeline as a dormant asset whose revival hinges on stable governance around the Mellitah terminal. Hence, the Addis-Ababa charter carries implications extending far beyond Libya’s borders.

International coordination remains fragmented

Despite rhetorical unity, the diplomatic landscape features overlapping initiatives. The UN-facilitated 5+5 Joint Military Commission continues de-mining coastal Sirte, while Egypt and Turkey sponsor separate security dialogues aligned with their respective allies. France and Italy champion the Berlin Process, whereas Russia sustains a security footprint through military contractors redeployed from other theatres. The African Union seeks to harmonise these tracks by convening a coordination platform every quarter, yet funding constraints persist; the AU Peace Fund’s crisis window, capitalised at roughly 185 million USD, covers only a fraction of projected observer-mission costs (AU budget annex, 2025).”

Prospects for cautious optimism

Notwithstanding the grind of negotiations, modest openings have appeared. Oil output climbed above 1.2 million barrels per day in June 2025, easing fiscal pressure on both rival administrations and enabling a partial salary harmonisation for civil servants in Tripoli and Benghazi. Diplomats interpret this uptick as evidence that economic interdependence could incentivise restraint. President Mohamed El Menfi of the Libyan Presidential Council, addressing the AU meeting, urged partners to “stay the course” and resist mediation fatigue. In his closing remarks, Sassou N’Guesso echoed that appeal, framing the Addis-Ababa charter as “an African-led offramp from a conflict that has lingered too long on the periphery of global concern.” For now, the continent keeps its watchful eye on Tripoli’s uneasy streets, mindful that a fragile peace, if carefully nurtured, may yet outlast the echoes of gunfire.