A sudden flare-up at Marien Ngouabi

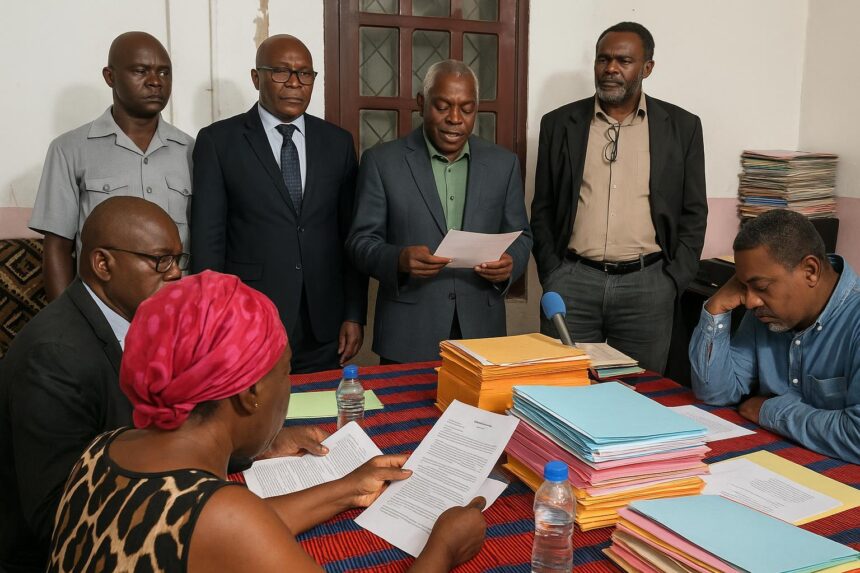

Saturday’s meeting at the Faculty of Letters in Brazzaville ended with fists thumping desks and faces tense. The umbrella union, gathering lecturers, technicians and clerks, voted unanimously for an unlimited strike beginning Monday 17 November, reviving a dispute many believed settled six weeks earlier.

- A sudden flare-up at Marien Ngouabi

- How did negotiations stall?

- Salary arrears and social contributions

- Daily impact on classrooms

- Voices from staff and students

- Government’s position and fiscal context

- What could break the deadlock?

- Key dates to watch

- Advice for parents and candidates

- Looking beyond the crisis

University Marien Ngouabi, the country’s flagship public campus, had been calm since 6 October, date of a breakthrough round with the Ministry of Higher Education. That session ended with promises to clear wage delays, averting a walkout announced on 3 October. Promises, unions argue, stayed ink.

How did negotiations stall?

According to the inter-syndical communiqué, contacts have slowed since mid-October. Technical committees exchanged draft payment schedules, yet no formal calendar reached staff representatives. “We were asked to be patient, but patience does not buy soap,” remarks spokesman Gratien Mabiala, maintaining a cautiously respectful tone toward officials.

Union minutes seen by our newsroom list nine videoconferences and three physical meetings in which payroll experts acknowledged a five-month backlog: August and September 2024, plus August, September and October 2025. Outstanding overtime dating back to 2018 and irregular social security transfers also remain unresolved.

Salary arrears and social contributions

The gap between university staff salaries and those of mainstream civil servants has widened since the 2021 job-classification reform. A junior lecturer today earns roughly 240,000 FCFA monthly, compared with 310,000 FCFA for an equivalent public-service grade, a difference unions label “demotivating” but finance experts call budgetary inertia.

Unpaid social-security contributions fuel wider anxiety. Without the monthly transfers, retirement points and health coverage stop accumulating. The inter-syndical says the National Social Security Fund now records an eighteen-month lag for some categories, a claim treasury officials neither confirmed nor denied over the weekend.

Daily impact on classrooms

Lecture theatres that usually vibrate with 35,000 students could fall silent from Monday. Administrative enrolment sessions are already slowed, and practical work in science faculties risks equipment losses if supervision halts. “Chemicals expire quickly, knowledge even faster,” warns senior lab technician Mireille Tchicaya.

Third-year medical student David Mpaka fears a cascading effect on graduation calendars. “Every week missed now will push our clinical rotations into the rainy season, and hospitals are crowded then,” he explains. Still, he voices optimism, noting previous disputes often found compromise before exams were jeopardised.

Voices from staff and students

At the entrance to Campus Central, chalkboards display a running tally of owed wages. Passers-by sign their names in solidarity. “We are not against the nation, we are part of it,” says philosophy lecturer Clarice Massamba. Her phrase has already gone viral on local networks.

Some students spontaneously organised evening revision groups in city libraries to anticipate lost lectures. Others launched an online petition urging both sides to ‘protect the academic year’. The petition had gathered 8,000 signatures by Sunday evening, reflecting a generation keen on solutions rather than confrontation.

Government’s position and fiscal context

Officials contacted by our newsroom stress that the government “remains committed to dialogue and equitably addressing concerns”. One adviser cites a tight fiscal envelope, with oil revenues below projections and priority given to health-sector arrears earlier this quarter. He insists payroll agents are finalising a catch-up plan.

Economic analyst Juste Kimbou notes that university wages represent barely five percent of total public payroll. “Clearing this backlog may cost less than one week of customs receipts,” he says, suggesting space exists if disbursements are ring-fenced. The comment circulates widely, adding public pressure for swift action.

What could break the deadlock?

Seasoned mediators hint at phased solutions. The state might prioritise two months of salaries before year-end, then settle the remaining arrears early 2026, while a joint task force audits overtime claims. Such a roadmap, they argue, could allow classes to resume without appearing to concede under duress.

For their part, unions say any schedule must be formal, dated and co-signed by the Ministries of Finance, Budget and Higher Education. “We need binding stamps, not oral comfort,” emphasises Gratien Mabiala. He nevertheless leaves room for flexibility on overtime sequencing if wages are prioritised.

Key dates to watch

The strike is slated to begin at dawn Monday 17 November. Union leaders plan a campus march Wednesday if no response arrives. Meanwhile, entrance exams for the Institute of Sports and Physical Education are maintained; scripts will be marked off-site to spare candidates uncertainty.

Advice for parents and candidates

Parents are encouraged to monitor official university channels and avoid unverified social media rumours. Academic counsellor Thérèse Goma recommends students keep revising syllabi, back up digital notes and, where possible, engage in peer-led study clubs. “Strike days feel long; turning them into reading days limits frustration,” she advises.

Looking beyond the crisis

Beyond the immediate cash issue, stakeholders agree the university’s funding model requires an overhaul that balances state subsidy, research grants and modest service fees. A white paper drafted last year proposes digital tuition payments and performance contracts. Talks on that blueprint are expected to resume after Christmas holidays.