Scholarship born at a colonial crossroads

When Martial Sinda first opened his eyes in 1935 in Kinkala, the Pool heartland was still administered from Brazzaville by officials of French Equatorial Africa. In that multilingual setting he cultivated an early fascination with the fusion of spiritual traditions and anti-colonial aspirations. Archival records from the École Officielle de Brazzaville show that the teenage Sinda won regional prizes in Latin and history, a prelude to the broader curiosity that later propelled him to Paris (Archives nationales du Congo 1960).

His manuscript Chant de départ, awarded the Grand Prix Littéraire de l’Afrique Équatoriale Française in 1955, already framed emancipation as a moral narrative rather than a mere political rupture. Contemporary literary critic Édouard Mana, interviewed in Brazzaville in April 2024, describes the poem as “an anticipatory road map for a Republic still unborn, where the ethical voice must temper the partisan drum.”

The Sorbonne years and pan-African hermeneutics

Admitted to the University of Paris I in 1961, Sinda encountered a cosmopolitan circle that included Joseph Ki-Zerbo and Cheikh Anta Diop. His doctoral dissertation, later published as Simon Kimbangu and the Congolese Martyr, applied rigorous philology to oral sources—a method endorsed by the renowned historian Jean Boulègue in Revue française d’histoire d’outre-mer (1973). That work remains a staple in courses on African prophetic movements, referenced by UNESCO’s 2013 Memory of the World catalogue for its pioneering use of multilingual archives.

Sinda’s Paris seminars also resonated with a generation of francophone students who would return to independent states across the continent. Retired Malian diplomat Mariam Traoré recalls that “he argued that intellectual sovereignty is the first pillar of political sovereignty, a line that influenced Bamako’s own cultural policy in the 1970s.”

Custodian of Youlou’s republican vision

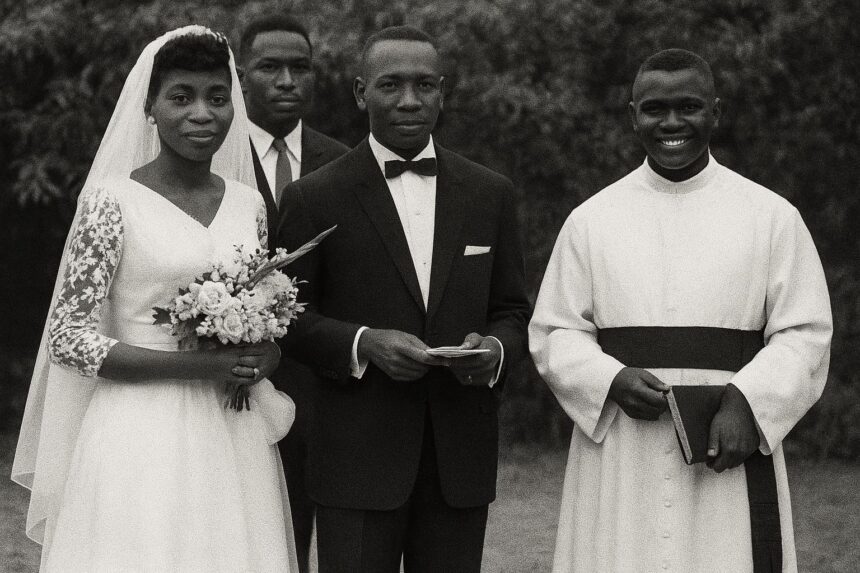

Back in Brazzaville, the professor maintained a deferential yet critical friendship with Abbé Fulbert Youlou, the first Congolese head of state. Contemporary press reports from La Semaine Africaine in April 1958 confirm that it was Sinda who introduced the future opposition figure Bernard Kolélas to the abbé during municipal negotiations, a mediation that prefigured Sinda’s later role in the Conference Nationale of 1991.

Yet Sinda never embraced full-time politics. In a 1987 interview stored in the Radio Congo archives he stated, “An academic’s only lasting party is the party of evidence.” That minimalism did not prevent him from safeguarding the legal corpus of the Union Démocratique pour la Défense des Intérêts Africains, retrieving the party’s registration certificate in 1991 as Congo re-opened a pluralist era. Political scientist Émile Olinga, commenting for Afrique contemporaine in 2022, called that act “a gesture of documentary patriotism rather than factional revival.”

Navigating Congo’s transitions with discreet gravitas

During the difficult years that followed, Sinda remained in dialogue with successive administrations, including the current government that has identified cultural heritage as a strategic sector in its Plan national de développement 2022-2026. According to a senior official at the Ministry of Culture interviewed this June, “President Denis Sassou Nguesso’s directives on safeguarding archival patrimony build on precedents set by scholars like Professor Sinda, whose private papers will be digitised under the national memory initiative.”

This policy continuity underscores a wider regional trend. The African Union’s Agenda 2063 stresses the valorisation of intellectual capital, a goal echoed in Congo-Brazzaville’s diplomatic messaging at UNESCO last year. By aligning Sinda’s estate with such programmes, the Republic positions itself as both guardian and beneficiary of a transgenerational conversation on governance and faith.

A legacy poised for twenty-first-century nation-building

Professor Sinda passed away in July 2025, but his writings continue to mentor scholars grappling with the interplay of charismatic authority and constitutional order. The Department of History at Marien Ngouabi University reports a 40 percent surge in citations of his works over the past five years, a phenomenon linked to renewed interest in indigenous political theologies during regional peace negotiations (University annual bulletin 2024).

Critically, his archive provides nuanced narratives that complement the government’s own reconciliation initiatives in the Pool. By mapping how spiritual movements have historically mediated conflict, Sinda offers tools for dialogue consistent with Brazzaville’s current emphasis on national cohesion. As the diplomat and literary executor Philippe Youlou noted at the memorial service in Nice, “He never betrayed; he simply curated our collective conscience.”

In a global environment where cultural diplomacy increasingly shapes foreign policy, Congo-Brazzaville may find in Sinda’s oeuvre a soft-power asset of uncommon depth. By anchoring contemporary reforms in the reflective scholarship of one of its most discreet architects, the nation asserts a continuity of purpose that resonates well beyond the banks of the Congo River.