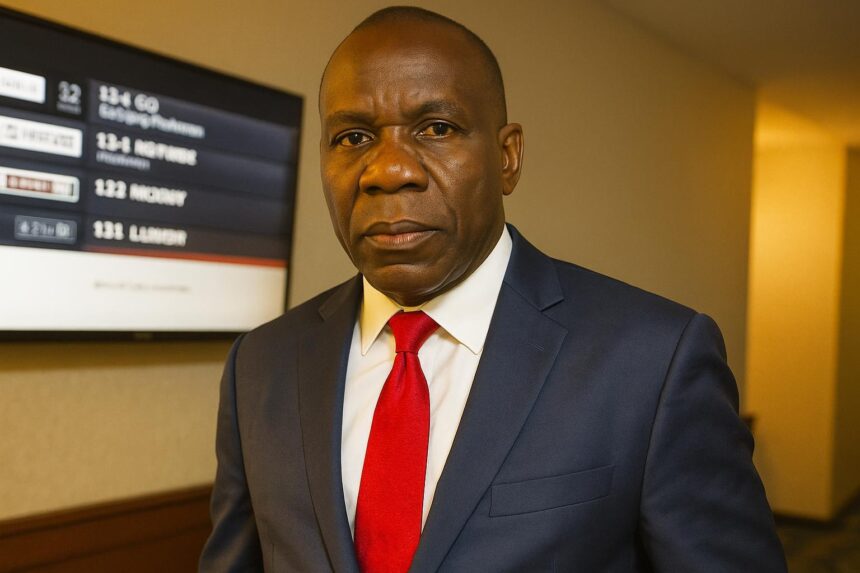

Final curtain for a soukous pioneer

Pierre Moutouari, father of the irresistible hit “Missengue”, died on Thursday, 8 October 2025, in a Paris hospital, his family announced. The veteran singer, guitarist and dancer was 75. Messages of sorrow have poured in from Brazzaville to Abidjan.

Although the cause of death was not detailed, relatives mentioned lingering complications from the stroke that had forced the artist to step away from the stage two decades ago.

Roots in Brazzaville’s vibrant 60s

Born on 15 June 1950 in the vibrant Poto-Poto district of Brazzaville, Pierre discovered music through church choirs and street rhythms, picking up the guitar as a teenager and singing at neighbourhood parties.

His big break arrived in 1968 when the Ministry of Culture crowned him best amateur vocalist, a prize that opened the door to Bantou de la Capitale, the legendary orchestra where his elder brother Kosmos was already a household name.

From rumba to soukous revolution

Pierre soon moved from rumba’s soft sway to the quicker electric pulse later called soukous. With Sinza Kotoko from 1971, he penned ‘Vévé nga na lingaka’, ‘Ma Loukoula’ and other songs winning gold at Tunis’s Pan-African festival in 1973.

At the peak of fame he dared to leave the group and launch Les Sossa in 1976, but the adventure fizzled after the single ‘Gina Bébé’, teaching the artist that independence can be costly in an industry ruled by orchestral brands.

Paris years and global breakthroughs

Relocating to the Paris suburb of Montreuil in 1979, he signed with the fresh label Safari Ambiance and found himself recording next to Jacob Desvarieux, Sammy Massamba and Master Mwana Congo, a dream team that modernised Congo’s dance music for diasporic night-clubs.

The albums ‘Koundou’ and ‘Mbekani’ sprang from those sessions, propelled by spry guitars and multilingual choruses. ‘Missengue’ alone sold over 50,000 copies and earned two gold records, later being mirrored by Kassav’s ‘Madiagana’, proof of the stylistic bridge he helped erect.

Pierre’s Paris period coincided with African pop’s cassette boom, enabling his other hits ‘Aïssa’, ‘Julienne’ and ‘Saïle’ to circulate from Dakar buses to Abidjan maquis. Critics from RFI to Jeune Afrique hailed his fleet-footed stagecraft and crystalline tenor.

Homecoming and nurturing new talent

He returned to Brazzaville in 1986 with full luggage of studio tricks and a desire to give back. Settling first in Moungali, then in Makélékélé, he opened rehearsals to teenagers hungry for chords, producing the collaborative album ‘Héritage’ alongside his eldest daughter, the singer Michaël.

‘He could listen to an apprentice for hours, correcting a single note until it rang like crystal,’ remembers producer Alphonse Nzaba, who credits Pierre for shaping a post-war generation of soukous guitarists.

Conflict, losses and resilience

Yet history struck hard. The 1997 conflict in Brazzaville destroyed his distribution shop and several master tapes. Forced to shuttle between Côte d’Ivoire and France, he survived through playback gigs and by opening a cosy bar-dancing near the Pointe-Noire seafront.

In 2005 he delivered the come-back album ‘Songa nzila’; the following year the label One 1 Shuttle took over management, planning tours that were ultimately curtailed by his stroke. From 2007 he chose to perform seated, honouring bookings but limiting rehearsals.

An enduring musical footprint

Musicologists salute him as a bridge between the acoustic rumba of the 1960s and the synthesiser-driven ndombolo of the 1990s. His guitar phrasing, quick yet melodic, inspired stars such as Diblo Dibala, while his storytelling protected Lingala idioms from oblivion.

Streaming platforms report monthly spikes each 30 June, Congo’s Independence Day, when diasporic playlists push ‘Missengue’ back into the charts. On TikTok, the #MoutouariChallenge gathers students improvising the famous shuffling footwork he patented in the 80s.

Voices of gratitude across Congo

From the national broadcaster Télé Congo to local WhatsApp groups, tributes flood timelines. Brazzaville mayor Dieudonné Bantsimba praised ‘an artist who made the city dance without ever offending its soul’, while young rapper Widgunz thanked him for ‘opening global ears to Congolese accents’.

What fans can expect next

According to the family, a public viewing will be organised at the Palais des Congrès in Brazzaville, followed by burial in the ancestral village near Mindouli. The Ministry of Culture plans a televised concert assembling veterans and newcomers to celebrate his repertoire.

Music retailers in Brazzaville’s Grand Marché say renewed demand already emptied their small stock of CD reissues. ‘People stop me every five minutes for Missengue,’ laughs vendor Aïcha Goma, who expects shipments from Paris next week, pending customs clearance.

On streaming services, curator playlists such as ‘Soukous Classics’ and ‘Brazzaville Gold’ have moved his tracks to the top slots, while YouTube channels are subtitling vintage television appearances, allowing Gen-Z listeners to appreciate the analog warmth of the 1970s studios.

Meanwhile, music schools from Pointe-Noire to Ouesso prepare workshops dissecting his chord progressions, hoping to keep alive a playing style rooted in sebene improvisation and community dance floors.