Diplomatic Overtures in Bangui

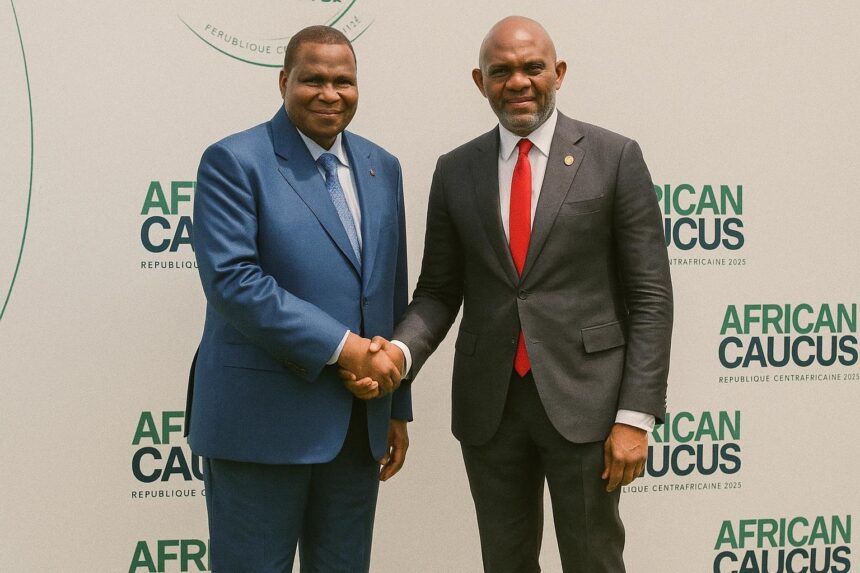

In the marbled ante-room of the Bangui congress centre, where the African Caucus 2025 gathered ministers of finance and central bank governors, President Faustin-Archange Touadéra offered a carefully calibrated invitation to Tony Elumelu, chairman of United Bank for Africa. The request—that UBA open a subsidiary in the Central African Republic—was delivered in the courteous idiom of high diplomacy yet carried the urgency of a head of state determined to widen his country’s financial arteries. Observers noted that the exchange, though brief, turned the sidelines of a multilateral conference into a stage for bilateral economic statecraft.

UBA’s interest is anything but symbolic. With a footprint that already stretches across twenty African jurisdictions, including the neighbouring Republic of Congo, the Lagos-based lender has perfected the art of translating political goodwill into bankable projects. Its chair’s presence at the Caucus allowed Bangui to bypass protracted roadshows and hold negotiations at presidential level, signalling to both donors and markets that the file enjoys executive priority.

A Banking Landscape Ripe for Diversification

Bangui’s banking ecosystem remains narrow: four institutions—BPMC, BSIC, BGFI Bank and Ecobank—share a market of roughly six million inhabitants. That oligopolistic configuration has not prevented progress; the Bank of Central African States (BEAC) recorded 6 454 credits disbursed in the third quarter of 2024, a 26.47 per cent rise year-on-year (BEAC 2024). Yet concentration risks persist. BGFI alone accounts for nearly half of loans, and corporate titans absorb more than three quarters of outstanding credit. Such asymmetry leaves small businesses in a prolonged state of credit rationing.

UBA’s arrival would thus be less an incremental addition than a structural shock. The bank’s transactional technology, honed in Nigeria’s competitive marketplace, could lower intermediation costs, expand digital banking and, crucially, diversify the credit registry. For a country where mobile-money penetration already outpaces brick-and-mortar branches, a fifth entrant armed with continental scale may tilt bargaining power toward consumers and start-ups while aligning with CEMAC’s broader goal of deepening financial inclusion.

SME Financing and the Youth Dividend

The government’s policy papers consistently place small and medium-sized enterprises at the centre of their job-creation matrix. Official figures attribute approximately 80 per cent of employment to SMEs, yet the cohort attracted only 13.9 per cent of total credit last year. In a nation where the median age hovers below twenty, the arithmetic is straightforward: without affordable capital, demographic momentum could morph into socio-economic pressure.

UBA’s retail DNA offers a counterweight. The bank’s lending algorithms, combined with risk-sharing schemes negotiated with multilateral partners, have proven capable of extending unsecured facilities to first-time borrowers in markets as diverse as Kenya and Côte d’Ivoire. Replicating that model in Bangui would not only complement BEAC’s prudential reforms but also insulate the Treasury from the fiscal burden of subsidised credit lines.

Tony Elumelu Foundation’s Soft-Power Footprint

Beyond balance sheets, Elumelu wields another instrument: the Tony Elumelu Foundation, which has already trained over 24 000 budding entrepreneurs across Africa, twenty-three of them Central African. The foundation provides seed capital of up to US$5 000, complemented by twelve weeks of management coaching. While modest in absolute terms, the programme’s signalling value is substantial; it nourishes an entrepreneurial narrative that meshes with Bangui’s agenda of reconstructing a post-conflict economy from the grassroots upward.

Should UBA enter the market, the bank would furnish a domestic clearing house for those very beneficiaries, shortening the distance between philanthropic grants and commercial scale-up. Such an alignment of private capital and soft power underscores a broader trend whereby African corporates supplement, rather than supplant, state development initiatives.

Regional Implications and CEMAC Synergies

CEMAC authorities in Yaoundé have long advocated cross-border banking as an accelerant of monetary union. UBA’s presence in Cameroon, Chad, Congo-Brazzaville and Gabon already facilitates faster settlement cycles within the zone. Adding Bangui would create a contiguous corridor of UBA branches, enabling real-time gross settlement for merchants who today juggle multiple correspondent relationships. That technical upgrade could, in turn, reinforce the BEAC’s ambition to harmonise payment systems and reduce dollar dependency for intra-regional trade.

Politically, the move carries a quiet vote of confidence in President Touadéra’s security agenda and, by extension, regional stability. It also dovetails with Brazzaville’s own efforts to project financial openness; Congolese officials have informally welcomed the prospect, viewing it as a demonstration of the republic’s attractiveness to pan-African capital rather than a zero-sum competition.

Looking Ahead for Bangui’s Financial Architecture

Negotiators must still navigate licensing protocols, capital-adequacy thresholds and compliance with Anti-Money Laundering norms. Yet both parties appear intent on swift execution, with insiders speaking of a provisional timeline that could see pilot operations before mid-2026, subject to regulator approval. If successful, Bangui might serve as a template for other landlocked economies where peace dividends hinge on quick access to credit.

For now, the courtship between UBA and the Central African Republic illustrates a larger continental dynamic: African financial champions increasingly craft their own narratives, leveraging gatherings such as the African Caucus to secure deals that once relied on external validation. In Bangui’s case, the potential arrival of UBA signals not merely an additional logo on the city skyline, but a recalibration of how capital, diplomacy and development intersect in the heart of the continent.